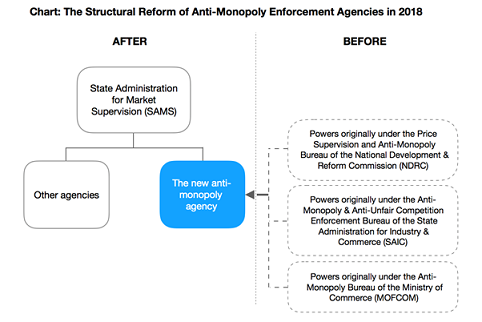

On March 13 2018 State Council Premier Li Keqiang submitted a proposal to the National People's Congress to review and consider the council's institutional reform programme. The proposal has shed light on plans to consolidate the antitrust enforcement powers of the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the State Administration for Industry and Commerce (SAIC) and the Ministry of Commerce under the State Administration for Market Supervision (SAMS) (Figure 1).(1) The programme was passed by the National People's Congress without delay and was officially announced on March 24 2018.

Figure 1

The merger, which will take place on the 10th anniversary of the implementation of the Anti-monopoly Law (AML), will likely bring changes to China's antitrust enforcement landscape. This update examines some of the reasons for the merger and the possible implications of the institutional reform programme.

The merger arose from China's eighth institutional reform, one of the highlights of which was the creation of SAMS, a unified market supervision authority, on March 21 2018.(2) According to Wang Yukai – an expert on China's administrative system reform – this institutional reform aimed to release the agencies from their management responsibilities with regard to specific issues (ie, what should be left for the market to solve will be left for the market to solve).(3)

Under the programme, China will establish five comprehensive enforcement task forces in order to consolidate various regulatory powers. These task forces will oversee comprehensive enforcement with regard to market supervision, ecology and environment protection, the culture markets, transportation and agriculture. Of these task forces, SAMS (the market supervision task force) has received significant attention, as it will combine administrative responsibilities concerning, among other things, industry and commerce, quality inspection, food and drugs, commodity prices, trademarks and patents, which will have a widespread impact on businesses.

The merger follows significant debate concerning whether China should have a single antitrust agency instead of its current three-agency model. Since the implementation of the Anti-monopoly Law in 2008:

- the NDRC and its authorised local subsidiaries have been responsible for enforcing price-related Anti-monopoly Law violations;

- the SAIC and its authorised local subsidiaries have been responsible for enforcing non-price related Anti-monopoly Law violations; and

- the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) has overseen the concentration of undertakings (ie, merger reviews).

Initially, it was claimed that this three-agency model would not create conflict with regard to enforcement. Shang Ming, the then-director of MOFCOM's Anti-Monopoly Bureau, argued that the enforcement powers of the three agencies had been clearly divided and that there would be no issue of overlap. However, he admitted that:

- there was a possibility that issues could emerge due to the similarities in the agencies' enforcement activities; and

- coordination and cooperation among the three agencies would be required.(4)

Despite these arguments, practitioners and scholars have advocated for a single unified antitrust agency in China for many years. These sentiments might reflect the observation that other major antitrust jurisdictions – such as the European Union, Japan, Hong Kong and South Korea – have adopted the unified competition enforcement agency model. The fact that the three-agency model has created inconsistencies in procedural and substantive matters might also have contributed to the drive for a single agency. For instance, the NDRC and the SAIC have been inconsistent in their issuance of penalties: whereas the NDRC has rarely invoked the confiscation of illicit gains provision when issuing fines for infringement, the SAIC has applied it in many of its infringement decisions. Concerns around the unclear delineation between price-related and non-price related violations have also been expressed.

There has been no official announcement as to when the merger will be implemented. However, the programme is expected to be implemented in different phases, starting at the central and provincial-government level, before being fully introduced in the prefectures, counties, towns and villages. Considering that the power to enforce Anti-monopoly Law violations has always been vested primarily in the state and provincial government agencies (with the latter being authorised by the former), a phased implementation may have less implications on the reform of the Anti-monopoly Law enforcement agencies, as this will occur in phase one.

Further, to date, there has been no official statement about a transition period for the reform.

On March 23 2018 Zhang Mao, the SAIC's original director general, was announced as the director general of SAMS. Reportedly, the staff of the new SAMS Anti-monopoly Law agency will comprise staff from the three original agencies. The head of the SAMS Anti-monopoly Law agency has yet to be announced.

The merger will likely result in a more stable Anti-monopoly Law enforcement agency and greater certainty and consistency with regard to Anti-monopoly Law-related practices in China. As such, businesses should have greater clarity with regard to how to carry out their compliance efforts.

Under the newly unified agency model, the previous confusion of whether a specific conduct, such as loyalty rebates, constituted a price or a non-price violation will be removed. This will expedite the handling of Anti-monopoly Law-related complaints on the regulator's part.

In the long run, the unnecessary inconsistencies in each of the parallel agencies' rules may also be eradicated. However, it is unclear whether the regulations and soft laws published or contemplated by each of the three agencies (either jointly or separately) will remain in effect. In this respect, a key question is how to harmonise the rules and practices concerning:

- the application of leniency and penalties;

- the safe harbour contemplated in the draft guidelines for the motor vehicle industry; and

- IP rights.

As mentioned above, although the merger is significant in terms of institutional reorganisation and the improvements that it may bring, it will not fundamentally change Anti-monopoly Law enforcement activities in China. That said, several issues are worthy of close observation, including:

- the way in which SAMS will carry out Anti-monopoly Law enforcement activities;

- the way in which existing regulations and soft laws will be applied in cases after the merger;

- SAMS's enforcement priorities; and

- the composition of the yet-to-be-formed Anti-monopoly Law agency.

For further information on this topic please contact Hao Zhan, Ying Song or Stephanie Wu Yuanyuan at AnJie Law Firm by telephone (+86 10 8567 5988) or email ([email protected], [email protected] or [email protected]). The AnJie Law Firm website can be accessed at www.anjielaw.com.?

Endnotes

(1) Further information is available here.

(2) Further information is available here.

(3) Further information is available here.

(4) Further information is available here.

This article was first published by the International Law Office, a premium online legal update service for major companies and law firms worldwide. Register for a free subscription.