1. Headline summary

2. Background

3. A brief recap of business interruption insurance

4. The key background facts

5. The policy wordings considered

6. The Court's conclusions

7. The implications of the judgment

The High Court has today handed down judgment in the COVID-19 Business Interruption insurance test case of The Financial Conduct Authority v Arch and Others. Herbert Smith Freehills represented the FCA (who was advancing the claim for policyholders) in the case, which considered 21 lead sample wordings from eight insurers. Following expedited proceedings, the judgment brings highly-anticipated guidance on the proper operation of cover under certain non-damage business interruption insurance extensions.

While different conclusions were reached in respect of each wording, the Court found in favour of the FCA on the majority of the key issues, in particular in respect of coverage triggers under most disease and 'hybrid' clauses, certain denial of access/public authority clauses, as well as causation and 'trends' clauses. The judgment should therefore bring welcome news for a significant number of the thousands of policyholders impacted by COVID-related business interruption losses.

Insurers relied heavily on Orient Express Hotels Ltd v Assicurazioni Generali SpA [2010] EWHC 1186 (Comm) in their submissions on causation. However, the Court distinguished it and considered that nothing in the analysis in Orient Express had any impact on the correct construction of the wordings it was considering. The Court did however say that if it had to rule on the case it would have determined that it was wrongly decided.

The proceedings were brought by the FCA, the regulator of the defendant insurers, as a test case. The purpose was to determine issues of principle on policy coverage and causation under sample insurance wordings.

The proceedings, commenced on 9 June 2020, were heard in July 2020 on an expedited basis under the Financial Market Test Case Scheme set out at Practice Direction 51M of the Civil Procedure Rules. The Scheme may be used for certain claims which raise issues of general importance in relation to which immediately relevant authoritative English law guidance is needed. Given the importance and urgency of the case, and as permitted by the rules of the Test Case Scheme, permission was given for the case to be heard by Lord Justice Flaux and Mr Justice Butcher sitting together.

The eight insurer defendants agreed to participate in the test case. The FCA represented the interests of the policyholders, many of which were small to medium sized enterprises. There were 21 sample wordings considered, but the FCA estimates that, in addition to these particular wordings, some 700 types of policies across 60 different insurers and 370,000 policyholders could potentially be affected by the test case.

The case was determined without live factual or expert evidence and on the basis of certain agreed facts (such as to particular steps taken by the Government). Extensive documentation, such as pleadings and submissions, was created for the test case and is available on the FCA website: https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/business-interruption-insurance#revisions. The trial was heard through Skype with members of the public able to watch via livestream.

Two action groups – the Hiscox Action Group and the Hospitality Insurance Group Action – were given permission to intervene on behalf of certain policyholders and present arguments in addition to those presented by the FCA.

3. A brief recap of business interruption insurance

Business interruption insurance will potentially cover loss of profits and additional expenses that an insured suffers as a result of insured damage to physical property such as following a fire or flood. Many policies, however, include specific extensions for matters other than physical damage. It is this non-damage business interruption cover that was squarely in issue here.

Business interruption policies will include wording that sets out how the insured's losses should be quantified by reference to matters such as the loss of profit / additional expenses incurred. They also typically contain "trends" clauses (or equivalent provisions in the quantification machinery) to allow for business trends that would have impacted the business anyway had the matters giving rise to the insurance claim not occurred. Precisely how these operate was again squarely in issue.

All will be familiar with the events of March 2020 and the practical implications of the steps taken by the Government. From a legal perspective, however, there was a particular focus on several key events:

- 3 March 2020: UK Government announces the UK COVID-19 action plan

- 5 March 2020: COVID-19 becomes a notifiable disease in England/Wales

- 11 March 2020: WHO declares COVID-19 to be a pandemic

- 16 March 2020: UK Government directs people to stay at home, stop non-essential contact and unnecessary travel, work from home where possible, and avoid social venues

- 20 March 2020: UK Government directs various categories of business to close, such as pubs, restaurants, gyms etc (given legal effect by Regulations coming into force on 21 March)

- 23 March 2020: UK Government announces lock-down involving closure of further businesses including all non-essential shops and restrictions on individual movement (given legal effect by Regulations coming into force on 26 March).

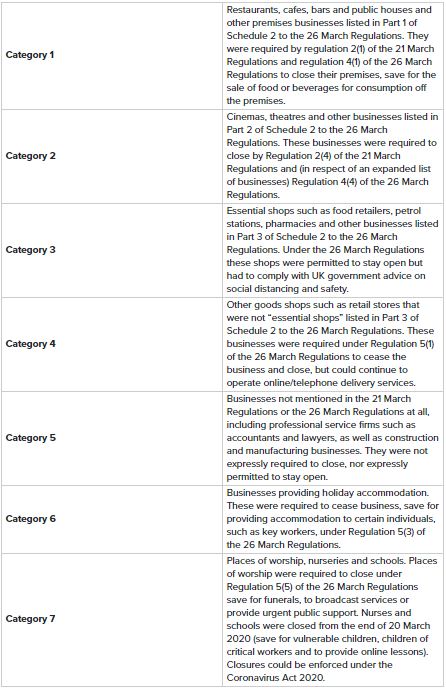

The steps taken by the UK Government did not impact all policyholders equally. While the statements on 16 March 2020 applied to all, the Regulations of 21 and 26 March imposed different requirements on different policyholders: the Regulations mandated that some businesses close, permitted others to stay open and were silent on others types of businesses. There were also separate regulatory provisions in relation to schools and churches and holiday accommodation. The FCA and Insurers agreed to categorise the policyholder businesses by reference to how they were impacted by the Regulations. The categorisation is found in the Appendix to this note.

5. The policy wordings considered

The parties agreed a sample of standard form business interruption policies for consideration in the case. A total of 21 lead policies were considered. The relevant provisions in the policies fell into three categories:

- Disease wordings: provisions which provide cover for business interruption in consequence of or following or arising from the occurrence of a notifiable disease within a specified radius of the insured premises.

- Prevention of access / public authority wordings: provisions which provide cover where there has been a prevention or hindrance of access to or use of the premises as a consequence of government or other authority action or restrictions.

- Hybrid wordings: provisions which are engaged by restrictions imposed on the premises in relation to a notifiable disease.

It will be apparent from the above that there were a number of different wordings and issues. This bulletin does not purport to cover each of the Court's conclusions, a number of which are nuanced and specific to the wording. The judgment should be carefully reviewed for such detailed analysis. What we set out below are the general themes emerging from the judgment.

The Disease Wordings

The policies in this category were written by RSA, Argenta, MS Amlin and QBE. Whilst they were all slightly different, they were, with two exceptions, in a form that provided cover for loss resulting from:

- interruption or interference with the business

- following / arising from / as a result of

- any notifiable disease / occurrence of a notifiable diseases / arising from any human infectious or human contagious disease manifested by any person

- within 25 miles / 1 mile / the "vicinity" of the premises / insured location

Two of the three QBE wordings were in a slightly different form, providing cover for "Loss resulting from interruption or interference with the business in consequence of any of the following events: … any occurrence of a notifiable disease within a radius of 25 miles" (QBE2) and "within a radius of one (1) mile of the premises" (QBE3).

Insurers argued that the cover provided was for a local occurrence of a notifiable disease. If, as here, there was a wider disease spread, then only the effects of the local outbreak of COVID-19 were covered, and only where they could be distinguished from wider effects (i.e. insurers argued that if "but for" the local disease there would have been the same interruption or interference there could be no cover).

The FCA argued this was incorrect. The FCA's case was that the correct causal test (that of proximate cause) would be satisfied where, as here, the COVID-19 outbreak in the relevant policy area was an indivisible part of the disease; alternatively that there were many different effective causes, namely the disease in a very large number of places.

The Court agreed with the FCA's analysis, concluding that the proximate cause of the business interruption was the notifiable disease of which the individual outbreaks form indivisible parts; alternatively (but less satisfactorily) each of the individual occurrences was a separate but effective cause of the national actions. The key factors leading to this conclusion were:

- The outbreak of disease is the "occurrence" of the disease. These clauses were triggered from the point in time at which there were cases of disease in the relevant policy area (the test generally being whether the cases were diagnosable, whether or not actually diagnosed or symptomatic).

- The insured peril is the composite peril of interruption or interference with the Business following the occurrence of the notifiable disease within the defined radius of the premises. The requirement for proximate causation is between the loss claimed by the insured and the composite insured peril.

- Whilst not central to the judgment, the word "following" where that appears as a causal link denotes a less than proximate causal connection, covering indirect effects of the disease. Even if the word "following" denotes the requirement of proximate causation, given the nature of the cover this would be satisfied in a case in which there is a national response to the widespread outbreak of a disease.

- Critically, cover was not limited to outbreaks wholly within the relevant policy area because (a) the wordings did not expressly state that the disease should only occur within the relevant policy area; the insured fortuity was notifiable disease which has come near the premises rather than discrete local occurrences; and (b) that construction is in keeping with the nature of the insurance in respect of notifiable disease. This is because those diseases which are notifiable include those capable of widespread dissemination, such as SARS and of a nature which will engage a response by national (not just local) bodies. Human infectious and contagious disease by its nature may spread in a highly complicated and fluid pattern. Cases within the relevant policy area are not therefore independent of, and a separate cause from, cases outside the relevant policy area.

The description of the relevant policy area as "Vicinity" in RSA's Marsh "Resilience" wording (RSA4), where Vicinity is defined as "an area surrounding or adjacent to an Insured Location in which events that occur within such area would reasonably be expected to have an impact on an Insured or the Insured's Business", was widely construed in the context of the disease clause as encompassing England and Wales. This was on the basis that, when COVID-19 occurred, it was of such a nature that any occurrence in England and Wales would reasonably be expected to have an impact on insureds and their businesses, and therefore that all occurrences of COVID-19 in England and Wales were within the relevant "Vicinity". (For undefined "vicinity" clauses – relevant to the Prevention of Access wordings, considered below – it was held to mean "neighbourhood" and to connote an immediacy of location).

The Court's conclusion was said to avoid the "anomalous" results that would follow from Insurers' position, namely that "there would be no effective cover if the local occurrence were a part of a wider outbreak and where, precisely because of the wider outbreak, it would be difficult or impossible to show that the local occurrence(s) made a difference to the response of the authorities and/or public."

The Court took a different approach, however, to two of the QBE wordings (QBE2 and QBE3), finding that the wording used in these policies (in particular the words "in consequence of" together with "events") had the effect that cover was limited to matters occurring at a particular time, in a particular place and in a particular way. Reference was made to the interpretation of "event" in other insurance cases such as in the aggregation case of Axa Reinsurance v Field [1996] 1 WLR 1026 in support of this reasoning. The limit of the radius to 1 mile for QBE3 further reinforced the Court's view that the parties had contemplated specific and localised events (albeit it should be noted that the fact of a 1-mile radius vicinity alone was not fatal to the claim – it was the construction of the provision overall that led to the Court's conclusion). Insureds would only be able to recover if they could show that the case(s) of disease within the relevant policy area, as opposed to elsewhere, were the cause of the business interruption. This may be relevant for some of the local lockdowns the country is now experiencing.

The Prevention of Access / Public Authority Wordings

The wordings in this category were written by Arch, Ecclesiastical, Hiscox, MS Amlin, RSA and Zurich. The wordings provide cover for loss resulting from:

- Prevention / denial / hindrance of access to the Premises

- Due to actions / advice / restrictions of / imposed by order of

- A government /local authority /police / other body

- Due to an emergency likely to endanger life / neighbouring property/incident within a specified area

The Court concluded that, generally speaking, these clauses were to be construed more restrictively than the majority of the Disease Clauses, albeit their findings provide for cover for some insureds under some wordings. The key factors considered by the court can be summarised as follows:

- The location and nature of the emergency/incident and the causal relationship between it and the relevant authority's action:

- The Court considered "emergency in the vicinity", "danger or disturbance in the vicinity", "injury in the vicinity" and "incident within 1 mile/the Vicinity" were all requirements that connoted something specific which happens at a particular time and in the local area. The court therefore concluded that such wordings were intended to provide narrow localised cover. As such, for cover to apply, the action of the relevant authority would have to be in response to the localised occurrence of the disease and action taken in response to the pandemic would not suffice.

- The nature of the actions/advice/order of the authority:

- The announcements by the Government on 16, 20 and 23 March were characterised as advice, rather than mandatory instructions, thus potentially engaging clauses with "advice" wordings. Similarly they could amount to an "action" in the context of a clause that contemplated hindrance of use.

- An "action" by an authority, which "prevents" access, requires steps which have the force of law, since only steps which have the force of law will prevent access. Similarly a restriction "imposed by order" conveys a restriction that is mandatory not merely advisory. As such, the Government's 16, 20 and 23 March advices were insufficient to trigger cover with such wordings although the Regulations issued by the Government on 21 and 26 March may trigger cover.

- The required effect of the authority's action on access to the premises:

- A number of policies required there to have been "prevention" of access (as opposed to, for example, "hindrance" of "use"). Where that was the case, although physical prevention was not required, there had to have been a closure of the premises for the purposes of carrying on the business.

- The required effect on the business:

- The Court considered that "interruption" did not require a complete cessation of the business but was intended to mean "business interruption" generally, including disruption and interference with the business. The exception to this general rule was in relation to MS Amlin 2, where interruption was given its strict meaning of cessation. This is because the reference to "interruption" was within the Prevention of Access clause ("We will pay you for… your financial losses and other items specified in the schedule, resulting solely and directly from an interruption to your business…") rather than in stem wording covering a number of insuring clauses which point to "interruption" including "disruption".

Whether cover is available to an insured under a Prevention of Access clause will therefore turn very closely upon the precise terms of the policy and the application of the government advice and Regulations to the insured's particular business, such as whether their business was directly mandated to close or was affected by the more general "stay at home" requirements. By way of example, the 26 March Regulations required restaurants to close but permitted them to continue to offer takeaway services. For restaurants that only offered sit-in food prior to the 26 March Regulations, the order could amount to a "prevention of access" because it closed the premises for the purposes of its existing business. By contrast, a restaurant that offered sit-in and (more than de minimis) takeaway services prior to the 26 March Regulations would only have its business partially impaired by the 26 March Regulations. As such, there may not be a "prevention of access". Two restaurants with the same "prevention of access" wording insurance cover, both of which have had to close their premises to sit in customers, could therefore find themselves with different coverage positions.

The Hybrid Wordings

The policies in this category were wordings from Hiscox and RSA. Again, there were variations between the wordings, but broadly they provided cover for losses resulting from:

- An interruption to the business

- Due to an inability to use the premises

- Due to restrictions imposed by a public authority

- Following an occurrence of disease

These clauses are a blend of a disease wording and prevention of access/public authority wording. The Court took a similar approach to the "disease" part of the clause to that set out above, rejecting Insurers' argument that the only cover was in respect of losses flowing from a local outbreak. However, as with the prevention of access wordings, the Court construed the meanings of "restrictions imposed" and "inability to use" narrowly, finding that "restrictions imposed" requires something mandatory, such as the mandatory requirements of the regulations, and "inability to use" requires something more than just an impairment of normal use. Therefore again, close examination of the particular terms of the clause is required to determine policy application.

Trends Clauses

The operation of trends clauses was a critical issue in the case. This is because, if construed in line with Insurers' arguments to include components of the insured peril itself, the application of the trends clause could effectively negate the value of any insurance cover available to the insured.

The starting point of the Court was as follows: the trends clause is intended simply to put the insured in the same position as it would have been had the insured peril not occurred. Where the policyholder has therefore on the face of it established a loss caused by an insured peril, it would be contrary to principle, unless the policy wording so requires, for that loss to be limited by the inclusion of any part of the insured peril in the assessment of what the position would have been if the insured peril had not occurred.

Therefore the extent of the insured peril becomes critical. Insurers contended that the insured peril should be narrowly defined. By way of example, in relation to a disease wording it was argued that the insured peril was the local occurrence of the disease alone and the other effects of the pandemic and associated government measures could be set up as part of the counterfactual (i.e. the facts once the insured peril is removed) as a business "trend" to reduce the claim. The result in practice may be that the insured's indemnity is negligible.

The Court had little sympathy with this argument, stating in relation to a hybrid Hiscox wording:

"… the FCA effectively illustrated the fallacy and unreality of the insurers' case in relation to the counterfactual, with particular reference to the Hiscox "public authorities" clauses, by focusing on the provision of cover in respect of an inability to use an insured's premises, assumed to be a restaurant, due to restrictions imposed on them by the local authority following the discovery of vermin dislodged from a nearby building site. On the insurers' case, the counterfactual involved stripping out the restrictions, but assuming the vermin were in the premises throughout, with whatever other consequences on the business the presence of vermin would have had. Thus, on insurers' case the insured could not recover in respect of the period after the imposition of the restrictions, unless it could show that customers not coming to the restaurant was due to the restriction imposed rather than due to the vermin, and that if the insured could not demonstrate that customers would have come despite the presence of vermin, it could not recover. As the FCA submitted, this would render the cover largely illusory, as insurers would argue that, as no one is likely to want to eat at a restaurant invested by vermin, all or most of the business interruption loss would have been suffered in any event. Such illusory cover cannot have been intended and is not what we consider would reasonably be understood to be what the parties had agreed to."

The Court provided the following guidance as to the 'in principle' operation of the trends clauses in respect of each category of wording:

- Disease wordings: The insured peril is the interruption or interference with the Business following the occurrence of the disease including via the authorities' or public's response. The wordings in issue insured the effects of COVID-19 both within the specified radius and outside it, with the result that the whole of the disease both inside and outside the relevant area has to be stripped out in the counterfactual.

- Prevention of access / public authority wordings: the insured peril is a composite one involving three interconnected elements: (i) prevention or hindrance of access to or use of the premises; (ii) by any action of an authority; (iii) due to an emergency / incident which could endanger human life. All three must be stripped out of the counterfactual.

- Hybrid wordings: The insured peril is also a composite peril involving (i) inability to use the insured premises; (ii) due to restrictions imposed by a public authority; (iii) following the occurrence of a human infectious or contagious disease. Each of these interconnected elements should be removed from the counterfactual.

It is also worth noting that a number of the Trends clauses were drafted so as to apply to losses from "Damage". On their face they did not apply to the non-damage extensions to the policy. Notwithstanding this, the Court concluded that it must have been intended that such clauses would apply to the non-damage extensions.

Causation and Orient Express

Insurers relied heavily upon the decision in Orient Express Hotels Ltd v Assicurazioni Generali SpA [2010] EWHC 1186 (Comm) to support their case on causation and the trends clauses. The Court found however that the issues of causation actually followed from the construction of the wordings before it and that Orient Express could be distinguished on matters of construction.

The Court nonetheless analysed the decision, given the reliance placed on it by Insurers. By way of recap, in Orient Express the claim was for business interruption losses caused by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. It was a claim under an all risks policy with a trends clause incorporating a "but for" causation test. It also had sub-limited prevention of access and loss of attraction cover. It came before the court as an appeal from an arbitral tribunal.

The premises in question were a hotel in New Orleans. There was no dispute as to cover for the physical damage to the hotel caused by the hurricanes. When it came to the business interruption losses, however, insurers argued that there was no cover because, even if the hotel had not been damaged, the devastation to the area around the hotel caused by the hurricanes was such that the business interruption losses would have been suffered in any event. Accordingly, the necessary causal test for the business interruption losses could not be met because the insured peril was the damage alone, and the event which caused the insured physical damage (the hurricanes) could be set up as a competing cause of the business interruption. Hamblen J held that this was correct.

As set out above, insurers in the test case contended for a narrow definition of the insured peril in the policy wordings (for example, on a disease clause wording, the local occurrence of disease only), in order to argue for the same result as in Orient Expresse. by setting up the widespread nature of the disease, and government advice and restrictions as a competing cause of the loss.

The Court dismissed Insurers' arguments and distinguished Orient Express on the basis that it was not concerned with the type of insured perils being considered in the case, in particular the "composite or compound perils" featuring in the wordings before the Court, contrasted with the "all risks" nature of the cover in Orient Express.

Notwithstanding this, the Court went on to say that they saw several problems with Orient Express. In their view, the decision misidentified the insured peril (by treating the "Damage" as the insured peril, rather than Damage caused by a covered fortuity – hurricanes) and the proximate cause of the loss was not "Damage" but "Damage caused by hurricanes". Further, the decision resulted in the absurd result that the more serious the fortuity the less cover was available: if the hurricane had only damaged the hotel, there would have been a full recovery. Accordingly, if it had been necessary for the case they would have concluded that it was wrongly decided and declined to follow it.

Prevalence

The Court did not make any findings of fact as to where COVID-19 has occurred or manifested. Whether the insured can discharge the burden of proving that the disease occurred or manifested in a certain area will need to be determined on a case by case basis. There are nonetheless some positive takeaways from the judgment for policyholders:

- Insurers conceded that the categories of evidence put forward by the FCA – specific evidence, NHS Deaths Data, ONS Deaths Data and reported cases – are in principle capable of demonstrating the presence of COVID-19;

- That a distribution based analysis, or an undercounting analysis (i.e. there are more cases than the reported cases), could in principle discharge the burden of proof on the Insured; and

- Insurers did not suggest that absolute precision is required and that otherwise claims will fail.

Whilst questions of fact therefore remain to be determined, the Court expressed its hope that, in the light of the concessions made by Insurers on the evidential questions of prevalence of disease, Insurers will be able to agree on any issues of prevalence which arise and are relevant to particular cases.

7. The implications of the judgment

The judgment will bring welcome news to a large number of policyholders, particularly those with Disease or Hybrid wordings similar to those considered in the Proceedings. Those with Prevention of Access / similar wordings may also find themselves with cover if the facts of their particular circumstances satisfy the requirements of their wordings. Clearly time will be needed to fully digest the judgment, but next steps for insureds will include considering (a) if any of the findings are directly (or indirectly) applicable to their wording; and (b) what additional issues will need to be considered to establish and prove a valid claim.

Appendix: Categories of business

For further information on this topic please contact Paul Lewis, Sarah McNally, Greig Anderson or Antonia Pegden at Herbert Smith Freehills LLP by telephone (+44 20 7374 8000) or email ([email protected], [email protected], [email protected] or [email protected]). The Herbert Smith Freehills LLP website can be accessed at www.herbertsmithfreehills.com.

This article has been reproduced in its original format from Lexology – www.Lexology.com.