This article examines a number of trademark cases before the Canadian courts in 2018.(1)

Scope of Canada's anti-dilution remedy

In Energizer Brands LLC v The Gillette Company (2018 FC 1003), the defendant (Duracell) brought a motion for summary judgment to strike certain allegations from the plaintiff's (Energizer's) statement of claim.

Duracell had made various comparative claims and used Energizer's registered trademarks ENERGIZER and ENERGIZER MAX, as well as the phrases 'the next leading competitive brand' and 'the bunny brand' on the labels of its Duracell batteries.

Although Duracell did not use Energizer's registered ENERGIZER BUNNY design trademarks on its packaging, the court refused to strike Energizer's claim, finding that:

the somewhat-hurried consumer seeing the words 'the bunny brand' in relation to batteries… would make both a link with and a connection to the ENERGIZER Bunny Trade-marks.

The remaining issue concerning whether Duracell's comparative advertising claims violated the Trademarks Act and the Competition Act will be heard by the trial judge. Although the matter was originally set down for a trial commencing 3 December 2018, this will be rescheduled for a later date. An appeal was filed on 14 November 2018 (A-357-18). On the other hand, Duracell's use of the phrase 'the next leading competitive brand' did not offend the Trademarks Act because no mental association had been made between Energizer's marks and the phrase 'the next leading competitive brand' which was used on Duracell's batteries. The court said that such an association "would involve imputing to the somewhat-hurried consumer details of market share in respect of which expert third-party evidence was filed in this Court". Therefore, these allegations were struck from Energizer's claim.

(For further details please see "Anti-dilution remedy not limited to registered trademarks".)

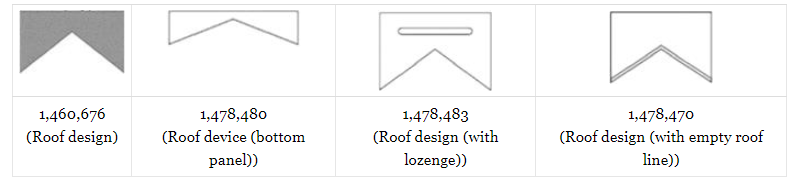

In Imperial Tobacco Canada Limited v Philip Morris Brands SARL (2018 FC 503), nine appeals of the Opposition Board's decisions rejecting Imperial Tobacco Canada Limited's (ITL's) oppositions to the registration of Philip Morris' (PM's) various design marks based on alleged confusion with ITL's registered trademark MARLBORO were heard together. The issue central to the appeals was whether the trademarks were confusing in light of new survey evidence filed on appeal.

With respect to the survey evidence, the court held it to be admissible in relation to one decision. It held that the rule in Mattel (ie, that the mark used in a survey be precisely the mark applied for), should be given a wider berth when a design mark is the subject of the survey.

The survey questions were not suggestive or speculative by presenting the design marks on a no-name getup as opposed to merely presenting the applied-for marks in isolation. As a result, this decision was reviewed on a correctness standard.

The court proceeded to consider whether there was a likelihood of confusion between each of the four applied-for design marks in this decision and ITL's registered trademark MARLBORO in light of all the evidence, including the new survey evidence.

For the remainder of the registrar's decisions, the survey evidence was considered to be inadmissible. These decisions were reviewed on the reasonableness standard and the appeals were dismissed.The court ultimately concluded that there was sufficient resemblance in the ideas suggested by the design marks and the word marlboro to establish a likelihood of confusion. The court allowed the appeal in part and directed that PM's trademark application number 1,460,676 (roof design) be refused and PM's trademark application numbers 1,478,480 (roof device (bottom panel)), 1,478,483 (roof design (with lozenge)) and 1,478,470 (roof design (with empty roof line)) be refused, but with respect only to the cigarettes.

Appeals were filed on 13 and 14 June 2018 (A-172-18; A-173-18).

Retail store services do not require bricks-and-mortars establishment

In Dollar General Corporation v 2900319 Canada Inc (2018 FC 778), the court reaffirmed that providing retail store services does not require a bricks-and-mortar establishment or direct delivery of products to Canada in order to constitute use of a trademark in Canada.

As long as there is a sufficient level of interactivity with potential Canadian customers (ie, Canadians receive a benefit), offering secondary or ancillary services on a website or an internet app, which are equivalent to what may be found in a bricks-and-mortar store, can constitute use of the trademark in connection with the provision of retail store services in Canada.

(For further details please see "No store, no problem: broad interpretation of 'use' advantageous for foreign retail trademark owners".)

Services performed in Canada without Canadian bricks-and-mortar location

In Hilton Worldwide Holding LLP v Miller Thomson (2018 FC 895), the registrar expunged a registration for the trademark WALDORF-ASTORIA for hotel services on the basis that the owner did not have a physical hotel in Canada and the only services which Canadians could access from Canada were hotel reservation services and a hotel loyalty programme. On appeal, the Federal Court overturned the registrar's decision to expunge Hilton's registration for the trademark WALDORF-ASTORIA in association with hotel services even though it did not have a bricks-and-mortar hotel in Canada.

In particular, the court held that the board had erred in ignoring the benefits provided to Canadians by Hilton (eg, the ability to book and pay via the website and collect loyalty points). The court reaffirmed its position that the term 'services' should be liberally construed and can include primary, incidental or ancillary services, which is consistent with Dollar General Corporation v 2900319 Canada Inc.

An appeal was filed on 5 October 2018 (A-325-18).

Consent letter from registered trademark owner insufficient to overturn registrar's decision

In Edmond de Rothschild v Canada (2018 FC 258), there was an appeal of an examiner's report refusing an application to register the mark EDMOND DE ROTHSCHILD in connection with a range of services, including financial services, on the basis that the mark was confusing with the registered mark ROTHSCHILD in the field of financial services.

On appeal, the applicant submitted new evidence that included consent from the owner of the cited trademark as well as evidence regarding the co-existence of the marks in the field of financial services in other geographic territories. The court held that the evidence would not have had a material impact on the registrar's decision and applied the reasonableness standard.

The court considered the consent to be of limited value, as the registrar must still consider its goal of protecting consumers by guaranteeing the origin of goods and services. While the registered trademark owner may not regard the marks as confusing, the court emphasised that it is the perspective of the average customer that must be assessed and not that of the owner of the cited mark. The court also rejected the evidence of co-existence in foreign jurisdictions as it did not discuss factors such as:

- the parties' trade channels;

- services offered; and

- the applicable legal test for confusion in other jurisdictions.

In reviewing the appeal on the reasonableness standard, the court noted that the marks solely consisted of words without any visual element to distinguish them and they would co-exist in the same market in which they would be the only two trademarks to share the term 'Rothschild'.

The court concluded that the registrar's decision fell within the range of possible, acceptable outcomes and dismissed the appeal.

Sales to employees at cost considered to be promotional in nature

In Herbert LLP v Cosmetic Warriors Ltd (2018 FC 63), the applicant appealed the registrar's Section 45 decision maintaining the registration of the trademark LUSH in association with t-shirts. On appeal, the Federal Court reversed the registrar's decision and cancelled the mark for non-use, holding that sales to employees of t-shirts bearing the mark did not constitute 'use' within the meaning of the Trademarks Act.

In particular, the court found that the transfer of t-shirts to employees at cost did not establish use in the normal course of trade:

I find that in the circumstances of this case, given the absence of profit, the promotional and de minimis nature of the sales to employees, and the fact that the Respondent is not normally in the business of selling clothing, the Registrar's determination… is unreasonable.

Further, in the absence of any profit, the sales were considered by the court to be primarily, if not exclusively, promotional in nature and not in the normal course of trade.

In addition to the sales to its Canadian employees, the respondent relied on its sales to its US employees and argued that, under Section 4(3), this was sufficient to maintain the registration as this Section does not require that sales must be "in the normal course of trade".

While the court agreed that Section 4(3) does not require use "in the normal course of trade", it emphasised that it is important not to lose sight of the purpose of this Section which is to:

protect Canadian entities who would be entitled to protection under the Act but for the fact that their sales place exclusively outside of Canada… where a party's activities do not establish use of a trademark, those same activities do not rise to the level of use because an export has taken place. A party cannot be allowed to make an end run around the normal requirements of the Act by shipping a product across the border.

The appeal was allowed and the court cancelled the registration.

An appeal was heard by the Federal Court of Appeal on 1 October 2018. The decision was reserved (A-70-18).

Appeal of 10 Opposition Board decisions filed

In American Express Marketing & Development Corp v Black Card LLC (2018 FC 362), American Express Marketing & Development Corp (Amex) filed appeals of 10 Opposition Board decisions in which the board had dismissed Amex's oppositions to applications for the trademark BLACKCARD and variations thereof. The applicant had withdrawn seven of its trademark applications before Amex filed its memorandum of fact and law.

The appeals dealt with the following issues:

- whether the appeals respecting the seven abandoned trademark applications were moot and, if so, whether the court should nevertheless exercise its discretion to decide them; and

- whether the trademarks were:

- confusing with Amex's unregistered BLACK CARD trademark;

- distinctive; and

- clearly descriptive.

New and material evidence was filed by Amex, which prompted the court to apply a standard of correctness in reviewing the board's decisions.

Mootness Amex's appeal concerned all 10 applications, even though seven of the applications had been abandoned following the board's decision.

Amex attempted to distinguish the present case from the general rule that the withdrawal of a trademark application renders moot the corresponding appeal. The court concluded that, although the three appeals regarding the pending trademark applications addressed issues in common with the appeals filed against the now abandoned applications, these decisions were to be decided on the record before the court and any future proceedings that may arise from the parties' competing trademark applications are to be decided according to their specific facts and on their own merits.

Therefore, the court held that the appeals regarding the seven abandoned trademark applications were moot and chose not to exercise its discretion to hear them out of concern for judicial economy and an awareness of the court's proper function in relation to the independent role of the registrar of trademarks.

Likelihood of confusion On appeal, Amex filed new evidence relying on an advertising campaign and a letter which had been sent to Amex cardholders concerning a mysterious black card. However, there was no evidence that Amex had commenced to perform any services in Canada in connection with a black card by the material date. Further, the court found that Amex's use was descriptive and not trademark use.

Non-distinctiveness Amex alleged that the respondent's trademarks were non-distinctive because they were:

- confusing with Amex's unregistered BLACK CARD trademark and black-coloured Centurion Card;

- descriptive because the respondent's credit cards were black in colour and third parties also issued black-coloured credit cards in Canada; and

- descriptive because a black card connotes a high-end charge or credit card.

Amex relied on new evidence in addition to that submitted to the board to demonstrate public association of black credit or charge cards with Amex's Centurion Card. However, the court found that Amex's evidence was insufficient to satisfy this ground of opposition.

Clearly descriptive Amex claimed that its marketing strategy had been to link the idea of exclusive services with black credit or charge cards and that the notion that black cards are high-end had attained widespread recognition in Canada. In assessing the issue of descriptiveness, the court stated that this must be assessed from the perspective of the average retailer, consumer or everyday user of the services in question. While the court found that the new evidence demonstrated that some Canadians associated black credit cards with prestigious or premium services, the evidence was insufficient to establish that the trademarks were 'clearly descriptive'. The use of the word 'clearly' implies that the impression created in the mind of the consumer must be self-evident or plain and this was not established by the evidence.

The decision was not appealed (T-1547-16).

Endnotes

(1) A review of 2018's notable patent cases is available here and a review of the life sciences and regulatory cases heard by the Canadian courts in 2018 and decisions on the merits is available here.

This article was first published by the International Law Office, a premium online legal update service for major companies and law firms worldwide. Register for a free subscription.