Thus far, biosimilar uptake has been low in the United States, with market shares for most biosimilars under 10%. Given the cost-saving potential, trying to increase biosimilar uptake has been high on Congress' agenda and there are many bills pending before it dealing with issues from a variety of angles, such as:

- changes to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Purple Book listing of biologic drugs;

- limits on patent litigation;

- changes to patent office proceedings; and

- ways to combat anti-competitive behaviour (eg, innovator product sponsors inappropriately withholding samples).

But will they actually help to bring biosimilars to market more quickly?

Using data compiled for BiologicsHQ.com, this article analyses two bills that propose changes to patent litigation by limiting the number of patents that a reference product sponsor (RPS) can assert in a patent litigation to see how many biosimilar cases they would have affected so far and whether they would really help to bring biosimilars to market sooner.

The Affordable Prescriptions for Patients Act 2019 (S1416) was introduced in the Senate on 29 May 2019 and amended on 27 June 2019. Its sponsors intended it to prevent 'product hopping' and 'patent thicketing' by codifying the definitions of these terms and considering them anti-competitive behaviours against which the Federal Trade Commission could take enforcement actions. In the amendment, the definition of 'patent thicketing' was removed and replaced with limits on the biologic drug patents that could be asserted in patent litigation. These same patent litigation limits are also included in the House version of this bill, the Affordable Prescriptions for Patients Through Improvements to Patent Litigation Act (HR3991), introduced on 25 July 2019.

Focusing on the provisions relating to biologic drugs, the Senate bill first defines 'product hopping' as an RPS making a 'hard' or 'soft' switch between the time that it receives notice that a manufacturer has submitted an abbreviated biologic licence application to the FDA and 180 days after the biosimilar has been marketed. According to the bill, such actions will be considered anti-competitive behaviour for which the RPS may be enjoined or disgorged of any unjust enrichment unless the RPS can demonstrate that one of the allowable pro-competitive, safety or supply disruption justifications apply.

A 'hard switch' is defined as when the RPS either:

- requests that approval for the reference product be withdrawn or that the reference product be placed on the discontinued product list and then markets or sells a follow-on product; or

- announces that it is withdrawing or discontinuing the reference product or destroys the inventory of the reference product in a manner that impedes biosimilar competition and then markets or sells a follow-on product.

A 'soft switch' is when an RPS takes actions (other than those defined as a hard switch) that unfairly disadvantage the reference product in a manner that impedes biosimilar competition and sells a follow-on product.

Both the House and the Senate bills place limits on certain types of patent that an RPS can assert against a biosimilar applicant in an infringement litigation if the biosimilar applicant completes all of the actions required of it under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) patent dance provisions (42 USC § 262(l)).

Under these bills, the RPS would be limited to asserting a maximum of 20 patents that claim a biological product, a use of that product or a method or product used in manufacture that also meet the following criteria:

- The patent must be disclosed on the list that the RPS gives to the biosimilar applicant as part of the patent dance (described in 42 USC § 262(l)(3)(A)).

- The patent must have an actual filing date of more than four years after the reference product was approved by the FDA or include a claim to a manufacturing process not used by the RPS.

In addition, no more than 10 out of the 20 patents could have issued after the RPS gave its list of patents to the biosimilar applicant during the patent dance exchange. The 20-patent limit does not include indication or method of use patents.

The 20-patent limit can be increased if it is in the interest of justice or the RPS can show good cause. Good cause is established if the biosimilar applicant fails to provide information required under 42 USC § 262(l)(2)(A) that would enable the RPS to form a reasonable belief about whether it could assert an infringement claim. Good cause may be established:

- if there is a material change to the biologic product or process;

- for a particular patent, if it would have issued prior to the RPS providing its patent list but for a delay by the patent office; or

- for another reason determined by the court.

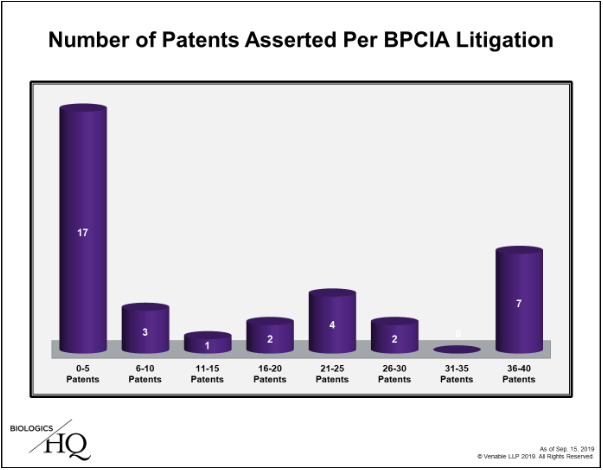

Limiting the patents that an RPS can assert during a patent litigation is likely to be concerning for patent owners, as this will arbitrarily impede their ability to assert their duly issued patents against a potential infringer and force them to limit their litigations to what they perceive to be their strongest patents prior to having fully conducted discovery on the biosimilar product. To determine how concerned patent owners need to be with respect to this litigation, below is an analysis of the 36 biosimilar-related litigations filed under the BPCIA to date which involve nine reference products to determine how many would have been affected if this law was already enacted.

While about two-thirds of cases asserted 20 or fewer total patents, 13 of the 36 cases (36%) asserted more than 20 patents. Removing method of treatment patents from the total (as these are not limited under the pending legislation), 10 cases (28%) could have been affected by this legislation based on the number of patents asserted. These 10 cases relate to three of the nine reference products (Avastin, Rituxan and Herceptin) and five biosimilars (Mvasi, Truxima, Herzuma, Kanjinti and Trazimera).

Since many of the biosimilar disputes under the BPCIA have involved multiple cases filed between the same parties relating to the same biosimilar, these 10 cases boil down to just five disputes: one each for Avastin and Rituxan and three for Herceptin. After removing the method of treatment patents, the greatest number of patents at issue in any case was 32, the majority of which covered manufacturing processes.

In order for the asserted patents to be included in the 20-patent limit, they must have an actual filing date of more than four years after the reference product was approved. When the earlier filed patents are removed from the totals in the 10 cases under analysis, no case has more than 20 patents at issue. Therefore, it is possible that none of the cases filed so far would have been affected by the pending legislation. However, without being able to analyse the manufacturing information for the reference products (which is not publicly available), it is impossible to say that no cases would have been affected, because patents including even one claim to a manufacturing process not used by the RPS are also limited to 20. This means that the legislation may have affected a limited number of patents.

Another important note is that the legislation's 20-patent limit applies only when the biosimilar applicant completes all of its steps in the patent dance. Patent owners in each of the disputes with more than 20 patents have alleged that the biosimilar did not complete all of the steps in the patent dance. Although the biosimilar applicants may have navigated the patent dance differently had this legislation already passed, it is possible this limitation would have brought these cases outside of the patent cap as well.

According to the above analysis, at least so far, patent owners may not have been significantly affected by these pending bills. Further, it appears that the enactment of the bills would not have likely sped up patent litigation or time to market by an appreciable amount. Although this is instructive, drawing any firm conclusions from this analysis may be dangerous, as IP protection surrounding RPS products are highly fact and technology-specific.

As drug pricing is high on Congress' agenda, there will likely be even more proposed legislation as different groups seek solutions. Currently, it is unclear which legislation will be passed, if any, and whether it will actually bring biosimilars to market more quickly. In this ever-changing landscape, it is important for patent owners and patent challengers to keep potential changes to the law in mind when conducting IP diligence on patent portfolios.

Patent owners should consider investigating which of their patents may be the strongest now in case limits are put on the number of patents that can be asserted in litigations. They should also carefully consider the timing of patent applications relative to biologic licence application filing in case limits are placed on patents that can be asserted based on when they are filed. Patent challengers should be mindful of how they navigate the patent dance and, in cases in which the exchanged lists include more than 20 patents, consider the impact of completing all of their obligations. Everyone should be mindful of the pending legislation and prepare early for anticipated changes in the law so that there is more time to mitigate unfavourable changes.

This article was first published by the International Law Office, a premium online legal update service for major companies and law firms worldwide. Register for a free subscription.