"That's the way the cookie crumbles", a panel of judges from the US Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit again concluded in rejecting trade dress protection for the well-known Pocky cookie design. However, in a revised decision following a rehearing request, the panel clarified its initial analysis on trade dress functionality, providing a fuller explanation of its reasoning which may soothe trade dress advocates.

More than 50 years ago, Japanese confectionery company Ezaki Glico Kabushiki Kaisha released Pocky – thin, elongated biscuits partially covered with chocolate (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Pocky eventually entered the US market. About five years later, Lotte Confectionery began selling Pocky lookalike biscuit sticks called Pepero (Figure 2):

Figure 2

Pepero did not go unnoticed. After obtaining US trade dress registrations for the Pocky design, Glico sent cease and desist letters to Pepero in the early-to-mid-1990s. Nevertheless, Lotte continued to sell Pepero.

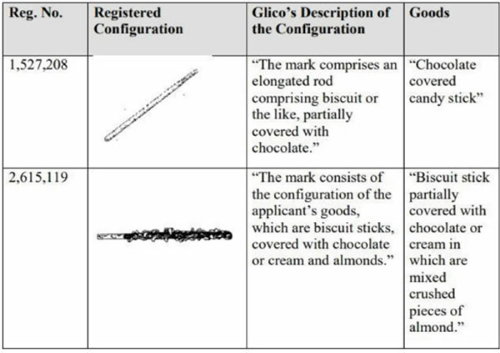

In 2015 Glico sued Lotte for trade dress infringement and unfair competition under the federal Lanham Act and state law in the US District Court in New Jersey. Glico based its claims on its two trade dress registrations for Pocky, which covered elongated biscuit sticks partially covered with chocolate (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Despite these two incontestable registrations, the district court granted summary judgment against Glico, deeming its Pocky design functional and not subject to trade dress protection.(1) The court cited Pocky's advertising over the years and a utility patent held by Glico as evidence of the design's functional advantages, which enabled "ease of consumption" and the sticks to be "packed close together" in a box. Glico appealed to the third circuit.

In its initial decision on appeal, a third circuit panel affirmed the lower court's decision, appearing to rule that any "useful" feature is inherently functional and thus not available for trade dress protection.(2) The panel began by clarifying its intention to "keep trademark law in its lane" by distinguishing it from copyrights and patents. It stated that "trademark law protects not inventions or designs per se, but branding". According to the panel:

[i]f the Lanham Act protected designs that were useful but not essential, as Ezaki Glico claims, it would invade the Patent Act's domain. Because the Lanham Act excludes useful designs, the two statutes rule different realms.

The panel also acknowledged that the goals of trademark law are "protecting the owner's goodwill and preventing consumers from being confused about the source of a product".

On the facts, the panel affirmed the lower court's finding that the Pocky design is useful because it "makes it work better as a snack", citing Glico's ads that referred to the "no mess handle" and "compact, easy-to-carry package" which holds "plentiful amounts of Pocky". It found Glico's evidence that many other cookie designs had been used in the field "relevant" but insufficient to overcome the other evidence of functionality. While it affirmed the lower court's ultimate functionality determination, it reversed the lower court's decision on the significance of Glico's utility patent, finding the patent "irrelevant" to functionality; the "innovation" in the patent was "a better method for making the snack's stick shape", not the snack's design.

Following the decision, Glico petitioned the third circuit for a rehearing en banc, with support from several interested parties, arguing that the panel's decision set the bar too low for finding functionality.

The third circuit denied the en banc request, but the original panel took the rehearing opportunity to issue a revised decision that provided additional clarity on its ruling.(3) It clarified that "[j]ust because an article is useful for some purpose, it does not follow that all design features of that article must be functional". It further explained that "[t]he question is not whether the product or feature is useful, but whether the particular shape and form chosen for that feature is".

The third circuit illustrated the point with case examples from the Supreme Court and recent appellate courts:

- "Though ironing-board pads need to use some color… there is no functional reason to use green-gold in particular."

- "Though French press coffeemakers need some handle, there is no functional reason to design the particular handle in the shape of a 'C.'"

- "And though armchairs need some armrest, there is no functional reason to design the particular armrest as a trapezoid."(4)

The panel summarised that "[i]roning-board colors, coffee-pot handles, and armrests are all generally useful. But the particular designs chosen in [the above] cases offered no edge in usefulness".

The panel also noted that "a combination of functional and non-functional features can be protected as trade dress, so long as the non-functional features help make the overall design distinctive and identify its source".

However, the panel also added a statement that Glico had "not borne its burden of showing nonfunctionality". This may cause further confusion because the panel had earlier correctly explained that the burden for proving functionality of registered trade dress like Pocky is on the challenger, not the trade dress proponent.(5)

On balance, the panel's modified decision may provide some comfort to brand owners, but whether the case is fully resolved will depend on whether a review is sought from the Supreme Court.

Endnotes

(1) Ezaki Glico Kabushiki Kaisha v Lotte Int'l Am Corp, 15-5477, 2019 WL 8405592 (DNJ 31 July 2019).

(2) Ezaki Glico Kabushiki Kaisha v Lotte Int'l Am Corp, 977 F.3d 261 (3d Cir 2020).

(3) Ezaki Glico Kabushiki Kaisha v Lotte Intl Am Corp, 19-3010, 2021 WL 253451 (3d Cir 26 Jan 2021).

(4) Qualitex Co v Jacobson Prods Co, 514 US 159, 166 (1995); Bodum USA Inc v A Top New Casting Inc, 927 F.3d 486, 492-93 (7th Cir 2019); Blumenthal Distrib Inc v Herman Miller Inc, 963 F.3d 859, 867-68 (9th Cir 2020).

(5) See 2021 WL 253451, at *5 ("The trade dresses are presumptively valid because they are registered and incontestable. See 15 U.S.C. § 1115. So Lotte bears the burden of proving that they are functional.") For unregistered designs, the trade dress proponent must prove non-functionality. See 15 USC § 1125(a)(3).