The government has published its response to the consultation on the sectors that will be subject to a mandatory notification regime under the National Security and Investment Bill.

The bill proposes to create a domestic investment screening regime in the United Kingdom (for further details please see "Global Britain? Rules, Britannia: Britannia screens the investment waves"). The regime would comprise:

- a mandatory screening regime for investment in certain core areas of the UK economy in which national security risks are considered more likely to arise;

- a voluntary regime in relation to investments in non-core areas, where these investments satisfy pre-defined trigger events; and

- a retrospective call-in right for the secretary of state, whereby the government will be able to call in and review transactions which it considers may give rise to national security concerns for up to six months from the date on which it learns of the transaction (subject to a 'long stop' date of five years of the date of the acquisition).

Notably, the call-in right will apply retrospectively from 12 November 2020. If the bill is passed in its current form, it will also – under the mandatory regime – become a criminal offence to complete a transaction without first obtaining approval from the secretary of state for business, energy and industrial strategy (currently Kwasi Kwarteng). Businesses could also be fined up to £10 million or 5% of their worldwide turnover (whichever is higher).

This article sets out an important reminder of what businesses need to be considering now in the context of this new screening regime, particularly in light of its retrospective nature.

As a result of concerns and suggestions made by businesses and investors during the consultation, the government has narrowed the definitions of the acquisitions within the sectors proposed as being within scope of the mandatory regime.

The government based its consultation on the following sectors:

- advanced materials;

- advanced robotics;

- AI;

- civil nuclear;

- communications;

- computing hardware;

- critical suppliers to emergency services or the government;

- cryptographic authentication;

- data infrastructure;

- defence;

- energy;

- synthetic biology;

- military and dual use;

- quantum technologies;

- satellite and space technologies; and

- transport.

Businesses considering transactions concerning entities active in these sectors should be aware that these transactions are likely to fall within the ambit of the mandatory notification regime. Further details on the notification process are expected to be published in the form of regulations following the passage of the bill into law, with the bill requiring that notifications are made in a prescribed format.

In the absence of details on the process for submitting mandatory notifications to the Investment and Security Unit (the new government body that will be responsible for undertaking national security screening), below are practical steps that businesses can take now to ensure that they appropriately manage the potential risks arising under this new regime.

What does this mean for potential investors?

The ambit of the proposed investment screening regime is broad; it applies where a trigger event occurs (ie, where the secretary of state reasonably suspects that there is – or could be – a risk to national security resulting from the acquisition of control).

Businesses that complete a transaction subject to the mandatory regime without prior approval risk fines of up to £10 million or 5% of their worldwide turnover (whichever is higher). For these purposes, worldwide turnover is inclusive of that generated by any businesses owned or controlled by the business that committed the offence. There is also the risk of potential imprisonment for individual acquirers or – where the acquirer is a company, partnership or unincorporated association – the officers of that body corporate (for up to 12 months on summary conviction or up to five years if convicted on indictment).(1) Transactions could also be unwound.

In view of the retrospective nature of the regime and the significant consequences of failure to notify a transaction, investors should already be self-assessing whether their transactions may be caught by the proposed investment screening regime.

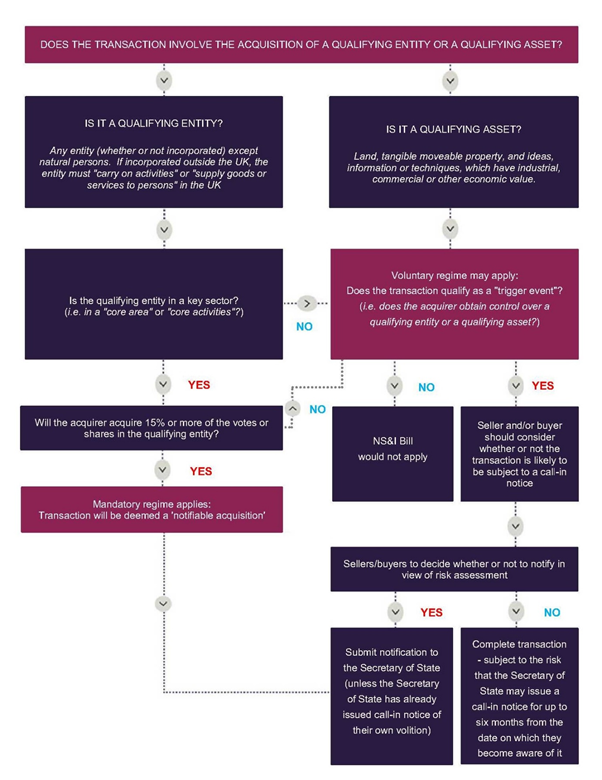

To assist businesses in their self-assessment exercise, Figure 1 sets out the steps that they should be taking to determine whether their transaction is at risk of falling within the ambit of the proposed regime.

Figure 1: how to assess transactions (from 12 November 2020)

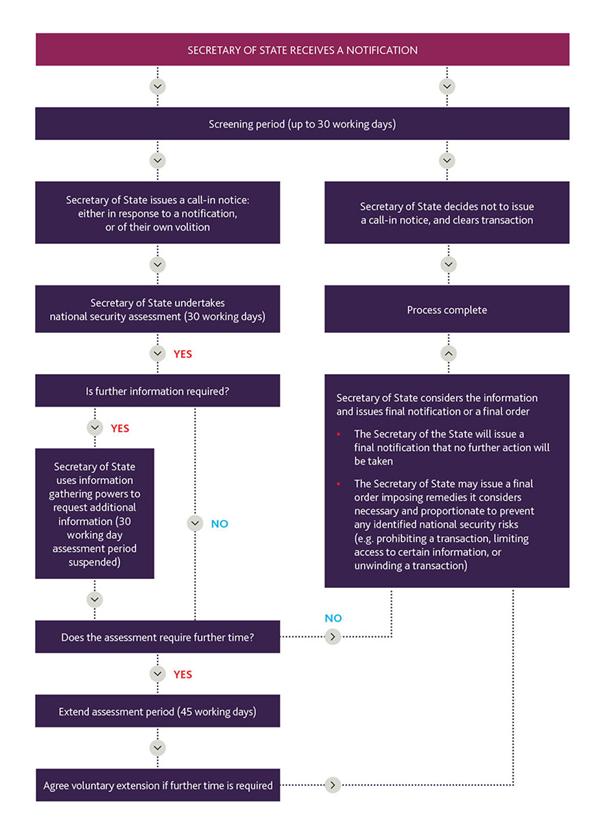

Figure 2 sets out the secretary of state review process. Investors should also note that until the bill enters into law, the secretary of state for business, energy and industrial strategy will continue to be able to intervene on national security grounds under the extant provisions of the UK merger control regime.

Figure 2: secretary of state review process

Although an established voluntary notification mechanism exists under the UK merger control regime, the government has not yet established any notification regime under the bill. The bill provides that the government may introduce new regulations that prescribe the form and content of any notice and may reject any notice that does not meet the requirements prescribed by the regulations.(2)

Absent a notification mechanism, the government has encouraged businesses whose transactions may be caught within the ambit of the new regime to contact [email protected] for "informal guidance".

While the government has not published formal guidance as to how to undertake the self-assessment exercise, it welcomes early engagement from investors and businesses and invites them to review the statement of policy intent, a copy of which can be viewed here.

When deciding whether to exercise its call-in right, the secretary of state must have regard to the statement of policy intent. The statement of intent identifies three types of risk:

- the 'target risk', which concerns the entity or asset which is the subject of the trigger event (ie, some assets and entities are more likely to give rise to a national security risk due to their nature);

- the 'trigger event risk' (ie, the potential of the underlying acquisition of control to undermine national security – for example, this may involve gaining control of a crucial supply chain); and

- the 'acquirer risk' (ie, national security concerns relating to a specific acquirer – for example, where the acquirer is hostile to UK national security or when it owes allegiance to hostile states or organisations).(3)

The government has also published a series of factsheets, which provide further information about each of the provisions in the bill.

However, uncertainty remains as to how 'trigger happy' the government will be in the exercise of its call-in right.

In view of the retrospective application of the secretary of state's review right, parties involved in transactions now need to be considering whether they may be caught by the new screening regime when the bill is enacted.

From a practical perspective, businesses should carefully plan their transactions and apportion risk by appropriately allocating responsibility within any transaction documents, especially if they operate within the proposed scope of the mandatory regime.

In the absence of any guidance on how this risk should be dealt with in transaction documents, businesses should consider:

- who should notify the secretary of state if a trigger event occurs that could give rise to a national security risk in line with the statement of intent (eg, acquirers, sellers or target entities). Transactions that fall within the mandatory regime will be subject to a mandatory notification requirement; and

- whether transactions should be conditional upon obtaining clearance.

Endnotes

(1) For more information, see Sections 32, 39(1) and 41 of the bill.

(2) For further information, see Sections 14(4), 14(6)(b), 18(4) and 18(6)(b) of the bill.

(3) For further information, see the statement of policy intent (2 March 2021).