Individual prosecutions under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) have markedly increased over the past five years. This increase in case law will help to better define local, regional and international enforcement.

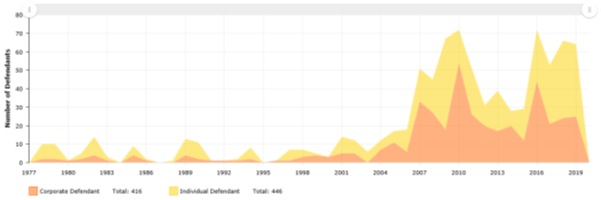

In the first half of the past decade, charges were brought against 84 individuals and 137 corporations. From 2015 to 2019, 144 individuals were charged, compared to 126 corporations.

The number of individuals charged represents a clear shift from 2010 to 2014 when approximately 38% of all FCPA charges were against individuals – that number rose to 53% over the past five years. Not only has the prosecution mix changed towards individuals, the absolute number of prosecutions of individuals has also increased. The average number of individual FCPA prosecutions per year has increased from 16.8 to nearly 29 over the same respective periods, while the number of corporate prosecutions has largely stayed the same, dipping slightly from an average of 27 to an average of 25. The following chart from the Stanford Law School FCPA Clearinghouse illustrates this shift.

This increased focus on individual prosecutions is a trend that is playing out worldwide, including in South and Southeast Asia. Businesses and persons from or operating in the region should especially take note. For example, in 2019 former Asia-based Goldman Sachs partner Tim Leissner agreed to a settlement with the Securities Exchange Commission and pleaded guilty to criminal charges as part of his role in the 1Malaysia Development Berhad scandal, which involved the payment of unlawful bribes to various government officials to secure lucrative contracts. That same year, Chinese national Jerry Li was charged with bribing government officials in China on behalf of his former employer, Herbalife, a New York Stock Exchange-listed multi-level marketing company. C-suite executives of S&P 500 technology company Cognizant also fell foul of the FCPA in South Asia, allegedly authorising $2.5 million in bribe payments to a government official in India according to a February 2019 indictment.

This increase in the prosecution of individuals has led to more FCPA trials, with at least four taking place in 2019 alone. Companies are naturally more hesitant to take cases to trial given the reputational risk, extensive legal costs and certainty of a financial payment and enhanced compliance measures in a settlement with the government. Indeed, the recent €3.6 billion Airbus resolution, despite lapping prior FCPA settlements in terms of the financial payment, has been hailed as precedential because it allowed the company to settle with three countries – France, the United Kingdom and the United States – in one fell swoop. Individuals, on the other hand, have liberty interests on the line, including the possibility of prison time. In addition, some individuals may have their legal fees advanced by their employers under indemnification agreements, which removes one incentive to settle.

So far, these courtroom challenges have had a mixed record of success for defendants. For example, in November 2019 Mark Lambert, former president of Transportation Logistics Inc, was convicted of four counts of violating the FCPA after a three-week trial in Maryland. The evidence at trial showed that Lambert had bribed a Russian official in order to secure contracts for his firm. Sentencing was set to take place in March 2020 but appears to have been delayed due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

However, with more cases being brought against individuals – and individuals being more willing to go to trial – FCPA case law is poised to develop significantly over the coming years. Judges may finally get the opportunity to decide the meaning and scope of many of the statute's key provisions, as well as associated legal theories that have been used in prosecution and defence.

Two trials that took place in 2019 reflect this pattern. In November 2019 Lawrence Hoskins was convicted of FCPA violations after a two-week trial in Connecticut. Hoskins's conviction marked the end of a lengthy prosecution, originally indicted in 2013 for acts that occurred between 2002 and 2009, that involved an interlocutory appeal to the Second Circuit. That appeal focused on whether the FCPA contemplated conspiracy and aiding and abetting liability for someone like Hoskins, a British citizen who had never set foot in the United States or been employed by a US company. The Second Circuit found that Hoskins could not be tried on conspiracy or aiding and abetting theories because there was no such liability without another basis for jurisdiction under the FCPA, but that he could be found criminally liable under an agency theory. Ultimately, that is what the jury found: Hoskins was an agent of the company's US subsidiary for which he worked even though he was employed by the parent company and never by the subsidiary.

After the jury verdict, Hoskins moved for acquittal based on insufficient evidence. In February 2020 Judge Arterton overturned the jury verdict as to the seven FCPA-related charges, finding that the Department of Justice (DOJ) had failed to present sufficient evidence that Hoskins was an agent of the US subsidiary. The government's appeal on the FCPA charges is pending in the Second Circuit, but Hoskins was sentenced to 15 months in prison on related money laundering charges in March 2020.

In a somewhat parallel case, Jean Boustani was acquitted by an Eastern District of New York jury in December 2019. Although not charged with FCPA violations himself, Boustani was charged with wire fraud and securities fraud as part of a scheme to sell Mozambican debt to investors that was supposed to be used for development projects. Significant portions of the loans' proceeds were actually used to pay kickbacks to Mozambican government officials and others involved. Boustani, a Lebanese citizen working for a UAE shipbuilding group who, like Hoskins, had never set foot in the United States, took the stand in his own defence and admitted to making the payments. Boustani's defence team argued in its opening statement that the United States is "not the world's policeman". That argument resonated with the jury, which acquitted him in five hours after a seven-week trial. Members of the jury said after the trial that they felt that the venue had been improper – the case's only connection to the United States was that illicit payments made had passed through correspondent bank accounts in New York.

These two trials have provided new guidance on the scope of the DOJ's ability to reach defendants with limited US connections. Another case, which is pending in the District of New Jersey, has shed some light on the unit of prosecution of the FCPA. Two C-suite executives of major US technology company, Cognizant, are being tried based on their alleged role in implementing and covering up a bribery scheme at an Indian subsidiary. Federal prosecutors charged one of the defendants, Gordon Coburn, with three counts of violating the FCPA – one for each email that he sent to alleged co-conspirators. Coburn argued that because there was only one bribe involved, he should be charged only once. In a 14 February 2020 opinion, US District Judge Kevin McNulty agreed with the government that the operative statutory language criminalised "making use of" interstate facilities such as email to facilitate a bribe, leading to his conclusion that Coburn could indeed be prosecuted for each email sent rather than the single bribe that he facilitated. As this was a novel issue, McNulty's opinion is a major step forward in demarcating how the government charges FCPA violations, but might not ultimately have any effect on the sentence that is imposed under US sentencing laws should there be a conviction.

Many individual defendants are still settling with the government rather than choosing to go to trial, in line with the pattern in most federal prosecutions in the United States. However, the fact that FCPA trials are now taking place may allow defendants to more credibly telegraph that they will not take a deal, potentially yielding better plea offers from the government. For example, Frank Roberto Chatburn Ripalda, who was originally charged under the FCPA, pleaded guilty on the eve of his trial to a conspiracy to commit money laundering charge. Prosecutors agreed to a reduction in the sentencing guidelines for acceptance of responsibility and Chatburn was ultimately sentenced to only three-and-a-half years in prison, despite facing a statutory maximum of 20 years. Chatburn's plea was part of a series of prosecutions relating to bribes paid to officials at PetroEcuador, Ecuador's national oil company. Another individual involved in the scheme, Armengol Alfonso Cevallos Diaz, also pleaded guilty just days before his trial was set to begin. Cevallos's sentencing is scheduled for the end of September 2020.

The DOJ's focus on individual prosecutions is "not an outlier or a statistical anomaly", as stated by former Assistant Attorney General Brian Benczkowski in a speech given on 4 December 2019 at the annual FCPA conference in Washington DC. From his remarks, it appears that this trend is likely to continue. What is less clear is what legal theories may or may not be available to the government as FCPA case law continues to develop. Benczkowski referenced the Second Circuit's Hoskins decision in his speech and reaffirmed that the DOJ will continue to use agency as a means of prosecuting FCPA cases – which the statutory language makes explicit as a basis for liability. However, Benczkowski also stated that "each case and application of agency liability will need to be evaluated on its own", refusing to make any delineation. He noted that agency liability is a fact-based determination, saying that "a person or entity may be an agent for some business purposes and not for others". In July 2020 the DOJ released a new version of its FCPA guide, updated for the first time since 2012, which briefly discusses the Hoskins case but, similar to Benczkowski's speech, provides no clear-cut position. With Benczkowski stepping down from his position and Brian Rabbitt now serving as acting assistant attorney general for the Criminal Division, it remains to be seen whether Benczkowski's statements will stand.

The DOJ seems to prefer leaving the law as open as possible until the courts can demarcate various boundaries, which they are likely to have the opportunity to do given the discussion above. Further, with more prosecutions of individuals and their willingness to take cases to trial, there is also the distinct possibility that cases might reach different outcomes in different circuits on the same issue. If circuit splits do arise, there is a small – but potentially growing – possibility of a first Supreme Court case interpreting the FCPA. Regardless, more FCPA case law shedding clarity on open issues will be a boon to lawyers, judges and scholars seeking to understand the contours of a complex statute – the elucidation of which has previously been almost the sole province of enforcers. It may also inform local and regional enforcement trends, including those in Southeast Asia, as regulators frequently look to their US colleagues' actions to inform behaviour.