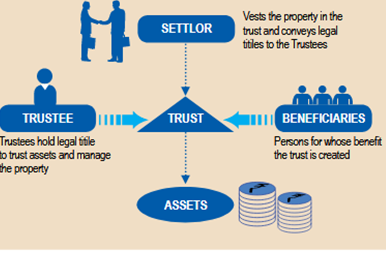

Private trusts are a popular tool among rich families with respect to succession planning. Trusts are a legal arrangement whereby assets are placed in the care of an individual who manages them for the benefit of someone else (Figure 1). Trusts can be further classified as specific or discretionary based on the scheme of distribution.

However, it appears that offshore trust structures are increasingly being used as a means of money laundering rather than lawful tax planning. Consequently, the Income Tax Department has unveiled various private offshore trusts and imposed tax liability on the beneficiary owners. This has led to an increase in reassessment proceedings and dissatisfaction among residents who claim that they have been subjected to wrongful tax liability.

In a recent case, the Mumbai Income Tax Appellate Tribunal (ITAT) provided relief to one individual, holding that offshore trusts are an acceptable form of tax planning and that a beneficiary of an offshore discretionary trust cannot be taxed on the entire corpus fund merely because they have been given the power to appoint or reappoint trustees.

Figure 1(1)

A search and seizure operation was conducted on Mr Yashovardhan Birla (the assessee) under Section 132 of the Income Tax Act 1961 for assessment years 2008-2009 to 2013-2014. On the discovery of undisclosed gold and diamond jewellery, a notice was served on the assessee under Section 16 of the Wealth Tax 1957. Pursuant to the notice, on 25 March 2015 the assessee filed his return on wealth for assessment year 2008-2009, declaring his net wealth to be Rs2,30,03,500 (almost six times the amount declared in the original return of wealth).

In addition, based on information received from the Foreign Tax and Tax Research division of the Central Board of Direct Taxes, it was discovered that the assessee was a beneficiary of more than 70 offshore bank accounts and immovable properties held by offshore entities. These offshore entities held these assets under an offshore discretionary trust, which had been created by the late Pratap Malpani in 1989 and was executed by an offshore trustee, Albany Trustee Company Limited. The list of beneficiaries included:

- the settlor;

- the settlor's wife, sons, daughters in law and lineal descendants;

- Ashokvardhan Birla (the settlor's brother in law) and his wife, Sunanda Birla (the settlor's sister), children (who included the assessee), children in law and lineal descendants; and

- charitable organisations in India and Guernsey.

The assessment officer labelled the amount held in these offshore bank accounts as being on par with cash in hand and classified them as unproductive assets under Section 2(ea) of the Wealth Tax Act. The assessment officer included a sum of Rs96,29,53,356/- in the assessee's net wealth.

The assessee filed an appeal against the assessment officer's order with the commissioner of income tax, but it was dismissed. As such, the assessee filed an appeal with the Mumbai ITAT.

The questions before the Mumbai ITAT were as follows:

- Was having a beneficial interest in offshore bank accounts held by offshore entities tantamount to being the ultimate beneficiary owner, resulting in the amount being included in the assessee's net wealth and the assessee being taxed accordingly?

- Was having the power to appoint or reappoint trustees the same as having control over the trust and the trust losing its independent identity? Further, could the entire corpus fund of the offshore discretionary trust with offshore trustees be included in the assessee's net wealth and net income when the assessee had never been allotted any share in the income or received any income from the trust?

The Mumbai ITAT rendered a comprehensive and detailed decision on the nature of the trust and the recitals of the trust deed. It noted that Malpani had created the trust for the benefit of several beneficiaries, including the assessee and charitable organisations. It held that the corpus of the trust could not be considered as part of the assessee's wealth for the following reasons:

- The trust was a discretionary trust under which the trustees had the absolute discretion to determine whether the amount therein should be distributed to the beneficiaries or retained by the trust. Hence, the beneficiary had no vested right in the corpus but merely a hope of receiving his share.

- The assessee was not the trust's sole beneficiary. The list of beneficiaries also included charitable organisations which meant that even if other beneficiaries did not survive, the fund would still not belong to the assessee alone.

- The trust had been created by a non-resident Indian using his offshore assets and no money or contribution had been transferred from India.

- During their lifetime, multiple beneficiaries had had the power to appoint trustees in certain situations. However, just because the assessee had exercised his power of appointing trustees did not put the trust in his ultimate control.

- The trust had an independent legal identity and the power of distribution of corpus still lay with the trustee and not with the assessee.

The Mumbai ITAT rejected the Department of Revenue's alternative contention of including the balance in the foreign bank account as cash in hand under Section 2(ea) of the Wealth Tax Act 1957. The Mumbai ITAT held that "there is no room for intendment in a taxing statute". The definition of 'assets' in Section 2(ea) lists cash in hand only as an unproductive asset and does not include the outstanding balance in offshore accounts as a separate category of asset, nor is it included in the explanation to the section. Differentiating between cash in an Indian bank account and cash in a foreign bank account by exempting the former from wealth tax and treating the latter as cash in hand would lead to an anomaly which was not intended by the legislature.

The Mumbai ITAT's reasoning is consistent with previous Supreme Court judgments wherein the beneficiaries of an offshore discretionary trust were exempted from taxation when the trust's income was retained by the trust and not disbursed to the beneficiaries.(2) The Mumbai ITAT looked not only at the declaration of the trust but also the reality of how the trust had been working. It provided clarity on other issues, including as follows:

- An assessment officer must supply reasons to an assessee for initiating reassessment proceedings. Non-disclosure of said reasons will infringe the assessee's right to defend themselves and vitiate the entire reassessment proceedings.

- The Income Tax Settlement Commission's decision in this case was not binding on the Mumbai ITAT as each case concerned different acts; the decision of the former was based on the Income Tax Act whereas the latter's was based on the Wealth Tax Act.

The taxability of offshore private trusts is a controversial issue. Although wealth tax was abolished from financial year 2015, the Income Tax Department has undertaken various assessments where it suspected that these trusts were being used to launder money. The question of the taxability of amounts in overseas discretionary trusts has also arisen under the Income Tax Act 1961. In other words, similar factual situations and arguments have been seen in tax evasion petitions wherein the Income Tax Department has included the corpus fund of such trusts in the net income of the assessee and imposed tax and penalties on that amount on the grounds that it was not disclosed by the assessee.

For instance, in the case of Manoj Duphelia,(3) the Mumbai ITAT included the amount held by a discretionary offshore Ambrunova trust in the net wealth and net income of the assessee, who was mentioned as a beneficiary but denied having any knowledge of being one. However, the Mumbai ITAT failed to address whether the Income Tax Act 1961 mandates such disclosure. Just because the trust had a bank account in an infamous tax haven and the assessee denied having knowledge of such trust did not infer that every account with the bank had been opened for tax evasion purposes. Further, a resident cannot be taxed on the corpus of a trust fund solely on the ground that they are a beneficiary. Although there is a thin line between tax planning and tax evasion, each factual scenario must be carefully examined.

Notwithstanding the fact that offshore discretionary trusts are an acceptable form of tax planning, they are frequently used for tax evasion purposes. In the White Label case, the Kolkata ITAT assessed the factual reality of the trust before determining whether the beneficiary should be taxed. All of the facts (ie, inability to prove the bank's appointment as a trustee, no official registration of the trust under Jersey law and no audit report of the trust's financial statement) led the Kolkata ITAT to conclude that the genuineness of the trust structure could not be verified and that the assessee had tried to escape taxation liability under the veil of an offshore trust.(4) Similarly, in the Tharani case,(5) the Mumbai ITAT lifted the veil off a discretionary trust. It took into account all of the incriminating factors (eg, the fact that the trust was based in the Cayman Islands, that the trustee company had been liquidated as soon as the Indian government had received information about the beneficiary, that the assessee denied any knowledge of the trust's existence and that the assessee was the sole beneficiary) and observed that:

the assessee is not a public personality like Mother Terresa that some unknown person, with complete anonymity, will settle a trust to give her US $ 4 million, and in any case, Cayman Islands is not known for philanthropists operating from there.

Hence, applying the rule of one size does not fit all, the legitimacy of an offshore trust should have to be verified on a case-by-case basis and the existence of incriminating evidence could lead to taxes being levied. Taxpayers must be able to provide a logical reason as to why they are a beneficiary of an offshore trust and why the settlor decided to make them a beneficiary of such funds – otherwise, they run the risk of being liable to pay tax.

Endnotes

(1) Image source: www.bcasonline.org.

(2) Commissioner of Wealth Tax, Rajkot v Estate of Late Hmm Vikramsinhji of Gondal (2014) 45 Taxmann.Com 552 (SC) and HH Maharaja Shri Jyotindrasinhji v Acit, 326 Itr 594 (SC).

(3) 2014 Taxmann.Com Mumbai Trib 52 146.

(4) Shri Som Dutt versus Assistant Commissioner Of Income Tax (2015) Taxmann.Com Kolkata Trib 60 59.

(5) Mrs Renu Tikamdas Tharani, Mumbai versus Dcit, Mumbai, Ita 2333/Mum/2018, 16 July 2020.