On 26 August 2019 the Trademark Review and Adjudication Board (TRAB), which is now part of the National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA),(1) released an analysis of its decisions that were challenged before the courts in 2018. In addition to this analysis, the TRAB provided comments on the admissibility of evidence in cancellation cases based on non-use for three consecutive years.

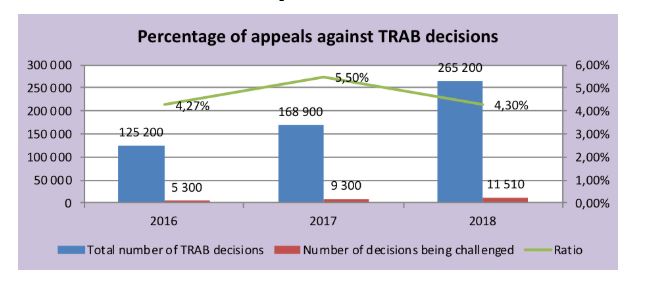

The total number of trademark cases adjudicated by the TRAB in 2018 was 265,200, a 57% increase compared with 2017 (168,900 cases) (Figure 1).

In 2017 the percentage of decisions challenged before the Beijing IP Court (first instance) was 5.5%. This dropped to 4.3% in 2018, which was almost on par with 2016.

Figure 1

The TRAB observed that despite the growth in the number of its adjudicated decisions in the past three years, the ratio of challenges has stabilised at around 5%, which indicates that the administrative agency and the judiciary have reached a consensus on major legal matters.

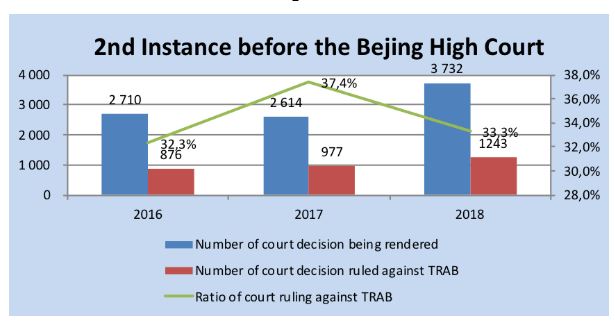

A total of 4,120 decisions were further challenged before the Beijing High Court and 420 decisions went all the way to the Supreme People's Court (SPC).

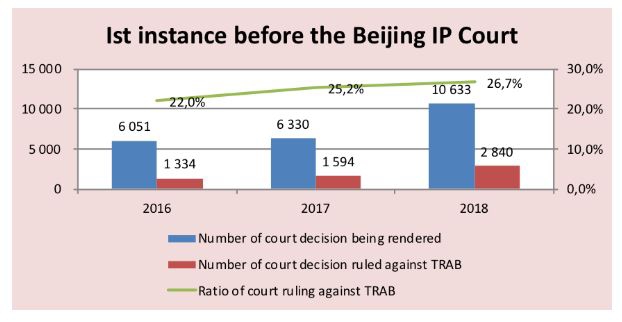

In 2018 26.7% of challenged TRAB decisions were overruled at first instance by the Beijing IP Court (Figure 2) and 33.3% of decisions appealed before the Beijing High Court were overruled (Figure 3).

Figure 2

Figure 3

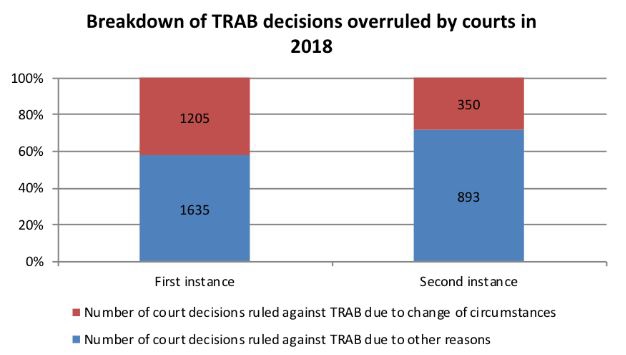

Of all of the decisions overruled by the courts in 2018, 1,205 in the first instance and 350 in the second instance were overruled due to a change of circumstances, accounting for 42.4% and 28.2% respectively (Figure 4). A 'change of circumstances' occurs when the prior rights (ie, trademarks filed or registered) cited by the China Trademark Office (CTMO) to refuse the registration of a trademark application are cancelled. Thus, the TRAB observed that, apart from decisions overruled due to a change of circumstances, the ratio of its decisions overruled by the Beijing IP Court was quite low (15.4%).

A change of circumstances may occur later, up to the SPC re-adjudication stage; of the 354 re-adjudication verdicts received, the SPC overruled the TRAB's decision in 35 cases due to a change of circumstances (9.9%).

Figure 4

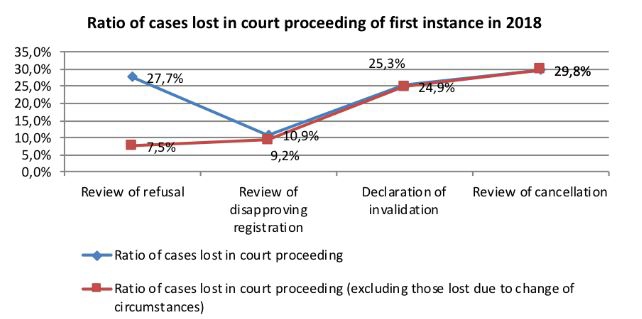

The TRAB proceeded with a more detailed analysis of why the courts had overruled its decisions, making distinctions between the types of decision concerned (Figure 5).

A review of refusal corresponds to the basic situation where a trademark application is refused by the CTMO due to absolute grounds or, most frequently, the citation of prior rights.

A review of disapproving registration corresponds to a scenario where the CTMO ruled in favour of an opposition and such decision was referred to the TRAB for review.

A declaration of invalidation corresponds to invalidation actions filed directly to the TRAB.

A review of cancellation corresponds to CTMO decisions concerning cancellation for non-use which are referred to the TRAB.

Figure 5 shows that TRAB decisions which review a CTMO decision rendered in favour of an opposition are rarely overruled by the courts. This percentage is even lower in cases of review of refusal if changes of circumstances are not considered.

Figure 5

However, the ratio of invalidation and cancellation cases lost in the courts is much higher, which insinuates that the agency disagrees with the judiciary regarding matters such as factual finding and the application of laws.

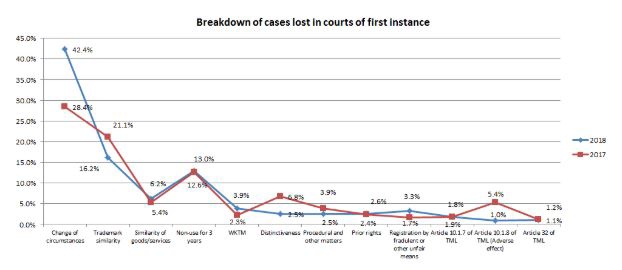

The TRAB gave a breakdown of the reasons why it lost cases in first-instance administrative litigation in 2018 and 2017 (Figure 6).

Figure 6

The ratio of cases lost due to a change of circumstances increased significantly in 2018, while that of cases lost due to trademark similarity determination dropped considerably in 2018.

The TRAB noted that a change of circumstances was the major reason leading to the overruling of its decisions by the first-instance courts.

This has given rise to the issue of the stay of procedure: if a TRAB decision on whether a trademark should be registered is directly contingent on whether the prior trademark cited by the CTMO remains valid or will be refused, invalidated or cancelled, why should the TRAB rush to confirm the refusal of the applied-for mark? Why not wait until the obstacles to the registration are lifted or the registration is confirmed as valid?

The TRAB rebutted the theory that the agency should suspend the adjudication of review-of-refusal cases where the legality of the cited marks is being challenged. Instead, it insisted that taking a decision without delay is an efficient and pragmatic practice that meets applicants' expectations regarding the swift granting of trademark rights and aligns with the rigid statutory time limit for its decision making. Such practice must be maintained after the agency has weighed the interests of various stakeholders.

There is still room for debate and, hopefully, constructive propositions.

First, it may be observed that in these types of case the issue is not to swiftly grant a trademark right, but rather to refuse it. Thus, urgency is not the issue.

Second, practice shows that as a result of the TRAB refusing to stay a procedure, an administrative case must be filed before the Beijing IP Court (and eventually the Beijing High Court or the SPC) in order to maintain the existence of the trademark application as long as the cited obstacles are not dealt with finally. This results in a lot of litigation, time and expense, all of which could be avoided if the TRAB waits to make its decision.

However, the TRAB was right when it observed that the law imposes strict time limits for its decisions. Thus, a solution to this conundrum could be that a decision to stay a procedure is considered a decision and therefore fulfils the requirements of the law. Once stayed, the case would be recorded in a list of pending cases and eventually dealt with when the circumstances have changed or it is confirmed that such circumstances will not change.

Determination of similarity of goods and services

The TRAB observed that the ratio of cases lost in court proceedings due to different findings in respect of the similarity of goods and services increased from 5.4% in 2017 to 6.2% in 2018. It mainly attributed this increase to inconsistencies in the judicial trial practice, exemplifying the conflicting findings of the Beijing IP Court (eg, where socks are found to be similar to apparel, footwear and hats in one case, but not in another).

The TRAB offered insight into the parameters that may help to determine a likelihood of confusion, including:

- similar marks (ie, identical, highly similar or similar);

- association between goods and services (ie, highly similar, similar or remotely similar); and

- other factors (eg, the prior mark is original and reputable or the contentious trademark registrant exhibits bad faith).

Admissibility of evidence in cancellation review procedures

The TRAB ascribed the overruling of its non-use cancellation review decisions to:

- the submission of new evidence in court proceedings; and

- its and the court's differing findings on the evidence of trademark use.

Therefore, the TRAB reiterated the following points.

The principles of preponderance(2) and the rule of thumb(3) set out in Several Provisions of the Supreme People's Court on Evidence in Civil Proceedings 2002 will be observed when trademark use evidence is scrutinised during a review of the cancellation of a trademark registration based on non-use for three consecutive years.

The TRAB commented on the admissibility of such evidence as follows.

Trademark licensing contracts Trademark licensing contracts merely prove that licensors and licensees have reached an agreement regarding the use of trademarks. The TRAB must still verify the execution of such contract so as to ascertain whether the licensee is genuinely engaged in the manufacture and sale of the products bearing the trademark. In the case of implied consent or verbal agreement where a licensor and licensee have a particular relationship (eg, parent and subsidiary or a legal representative with control over a company), the trademark use act of the de facto licensee will not be dismissed merely based on the fact that no trademark licensing contract exists.

Commissioned processing evidence Commissioned processing evidence merely proves that a user has prepared to use a trademark. In general, without further evidence corroborating the sale of products bearing a contentious trademark to end consumers, the TRAB tends to find that such preparation does not constitute use of the contentious trademark, given that the mark fails to function as source identifier of the products to which it is attached. Original equipment manufacturers are an exceptional circumstance that the agency did not address in its analysis.

Product sales evidence Sales contracts must be accompanied with evidence of execution. In principle, notarised online sales records obtained from independent e-commerce platform giants such as Taobao and JD will be deemed genuine.

Physical and graphic evidence

In principle, the TRAB found that physical and graphic evidence is of low probative value, given that it is easy to forge and tamper with.

The TRAB also highlighted the key parameter for ascertaining the use of service trademarks – namely, evidence is eligible only if it can prove that the service is provided to recipients other than the service provider, per se.

This article was first published by the International Law Office, a premium online legal update service for major companies and law firms worldwide. Register for a free subscription.

Endnotes

(1) For pure convenience, this article continues to call it the TRAB, although it is now referred to as the CNIPA, as well as the CTMO, which is also called the CNIPA.

(2) Article 73 of Several Provisions of the SPC on Evidence in Civil Proceedings provides that if the parties to a case produce conflicting evidence on the same fact but neither has sufficient evidence to rebut that of the other party, the court will assess whether the evidence submitted by one party is clearly more persuasive than that submitted by the other, taking into consideration the circumstances of the case as a whole, and subsequently affirm which party's evidence has greater probative value. Where it is unable to judge the probative force of evidence, thus making it difficult to ascertain the disputed fact, the court will make its ruling according to the rule on the distribution of the burden of proof.

(3) Article 64 of Several Provisions of the SPC on Evidence in Civil Proceedings provides that judges will:

- assess the evidence on a thorough and objective basis in accordance with applicable legal procedures;

- adhere to the professional ethics of judges; and

- use logical reasoning and their experience to reach independent judgments concerning the probative value of evidence.