In the fight against climate change and further to the 2015 Paris Agreement (under which 195 governments have agreed to take concrete measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions globally and set sustainable development goals), the Italian government ratified the Italian National Energy Strategy (INES) in 2017.(1)

The INES's main aims are to:

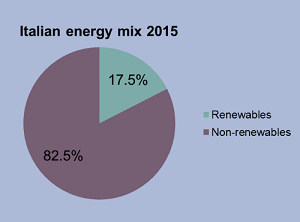

- reverse the trend of 2014 to 2017, which saw the share of power supplied from renewable energy decline in Italy, mostly due to reductions in renewable incentives;

- phase out coal in electricity generation by 2025; and

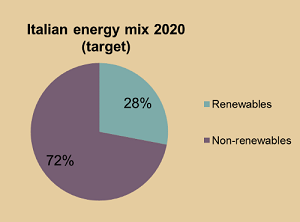

- raise the share of renewable energy in Italy's energy supply from 17.5% in 2015 to 28% by 2030, with a share of 55% for renewables in electricity generation and 21% in transport.

Given this background, corporates in Italy and worldwide have set goals to:

- limit their greenhouse gas emissions;

- reduce their environmental footprint and energy costs; and

- contribute to the renewable energy targets set by their governments.

One way to reach these goals is through the use of corporate renewable power purchase agreements (PPAs), which are contracts between buyers (off-takers) and power producers (ie, developers, independent power producers or investors) to purchase electricity at a pre-agreed price for a pre-agreed period.

The INES highlights that corporate PPAs may facilitate the development and bankability of new, large-scale renewable energy plants. Corporate PPAs are also mentioned in the draft of a new decree-law,(2) which provides incentives for producing renewable energy over the next three years. However, this is still to be approved by the European Commission and, if approved, it will then need to be issued by the Ministry for Economic Development.

The draft decree-law considers corporate PPAs an alternative to public incentives and proposes creating a market platform to be managed by the Gestore dei Mercati Energetici Spa to facilitate long-term contracts for renewable energy. It also proposes that the Italian Regulatory Authority for Electricity and Gas prepare a standard term sheet for long-term corporate PPAs.

Going forward, the next steps are to:

- include corporate PPAs in the national electricity regulation;

- remove direct and indirect regulatory barriers for corporate PPAs;

- design compatible renewable support schemes;

- establish renewable certificate systems; and

- facilitate dialogue between interested parties to foster the mutual understanding of possible solutions.

Drivers for committing to corporate PPAs

The main drivers for corporate buyers to commit to a long-term corporate PPA can be broadly described as economic, sustainability and reputational factors.

From an economic perspective, a long-term fixed-price corporate PPA is a hedge against power price volatility and may also avoid long-term carbon and environmental penalties by complying with current and future regulatory requirements. Sustainability is also an important driver insofar as corporates are keen to reduce carbon emissions and contribute to national renewable energy targets. Committing to corporate PPAs may also be useful to enhance a corporate buyer's reputation and brand leadership, as this may help them to get recognition for renewable electricity achievements and meet their public sustainability commitments.

Moreover, developers and lenders may perceive a long-term corporate PPA (especially if it is on a price-fixed basis) as a risk mitigation tool to:

- diversify revenue streams from traditional utility off-takers;

- ease bankability with financial institutions, thanks to the predictability of long-term income streams; and

- create new demand for energy from a business development perspective.

Common contractual structures of corporate PPAs

One type of corporate PPA is a 'sleeved' or 'physical' PPA. This is a purchasing contract that may be executed if:

- the plant is located on the same grid network as the corporate's off-take point; and

- the electricity is sleeved by the utility from the generation plant to the buyer.

A sleeved or physical corporate PPA is the most commonly used contractual structure in Italy. Under this scheme, the corporate buyer simultaneously enters into a PPA with the developer and a back-to-back PPA with its incumbent utility.

One characteristic of this type of corporate PPA is that it requires the utility to physically deliver power to the relevant site for the corporate buyer, which is not permitted to off-take the power directly under local electricity supply rules. Instead, the developer transfers the electricity to the utility, which will sleeve it through the grid to the corporate buyer.

The parties may also agree that physical delivery is not required. This is called taking a 'virtual', 'synthetic' or 'financial' approach.

Virtual PPAs are financial derivatives (such as contracts for difference), where generators and off-takers agree to a strike price that will be paid for each unit of energy generated over an agreed period. The project sells the power to the open market and the off-taker purchases power from the open market. If the market price rises above the strike price, then the developer pays the difference to the off-taker. Conversely, the off-taker compensates the developer in the event that the market price falls below the strike price.

Similar financial structures may be created through the use of call and put options. For instance, put options would give the developer the opportunity to buy the right to sell the generated energy at a certain strike price. If wholesale power prices fall below the strike price, the developer can exercise its option to sell the electricity at a higher strike price.

Key corporate PPA risks and how to mitigate them

There are numerous risks to consider before entering into a corporate PPA, including:

- market risk;

- price and project revenue risk;

- tenor risk;

- currency or foreign exchange risk;

- credit risk;

- scheduling risk;

- basis risk;

- balancing risk;

- volume risk;

- shape or profile risk;

- construction risk;

- performance or operational risk;

- change in law risk; and

- force majeure risk.

The table below includes a brief description of the risks noted above and how those risks may be mitigated.

|

Type of risk |

Details |

How to mitigate risk |

|

Market risk |

Agreeing to a purchase price for power over a long period could be risky if electricity prices decrease. Although unlikely, this could happen because of new technologies, regulatory changes, better transmission capabilities, a combination of these factors or for other reasons. |

To mitigate market risk, corporate buyers should consult a market expert and consider power price forecasts. |

|

Price and project revenue risk |

Corporate PPA pricing structures may be fixed (an agreed price per MWh with no escalation over time) or flexible. For example, the parties may agree to a price increase over time linked to inflation or wholesale power prices. The parties may also agree to set the price at a fixed discount to the fluctuating wholesale power price, perhaps with a cap and floor, so that if the wholesale price drops below the latter, the corporate buyer pays the floor and if the wholesale price increases above the cap, the corporate buyer pays only the cap. |

To mitigate price risk, if the price of power is expected to decrease, a corporate buyer should opt for a flexible pricing mechanism. In general, developers will almost always benefit from a long-term, highly predictable pricing mechanism, whereas lenders will want a fixed price in order to ensure that the project's revenues are certain and will be sufficient to repay any loans. Lenders traditionally manage project revenue risk using a range of tools, including:

Flexible and innovative solutions exist to balance the requirements of the various parties to a corporate PPA, including:

|

|

Tenor risk |

Tenor risk relates to the period over which the corporate buyer must pay for power contracted for under the corporate PPA. It can be a fixed-duration period or a period that is subject to extensions triggered by certain conditions. For power produced by an existing renewable energy plant, the term of a corporate PPA in Italy is usually short (one to five years). By contrast, for power produced by a renewable energy plant that is under construction, the term of the corporate PPA is usually longer (10 to 15 years). With a fixed price comes the possibility of significant savings (if power prices increase) and the risk of being locked into a higher than market price (if power prices decrease). |

The corporate buyer's position on tenor risk will depend on its:

Developers will be guided both by lenders' minimum-term requirements and by power price forecasts. Lenders will expect that corporate PPAs cover at least the term of the loan being contemplated and preferably also include a tail period after the maturity date, especially when the lender is providing a high proportion of the capital to finance a new project. Put and call mechanisms may be implemented to balance the expectations of the various parties to the corporate PPA. For instance, if the wholesale power price goes up, the corporate buyer may be granted the option to extend the term at a higher price. If the wholesale power price goes down, the developer may be granted the option to extend the term at a lower price. In these scenarios, the put and call prices are fixed in advance, applying acceptable caps and floors. |

|

Currency or foreign exchange risk |

This risk arises because of the mismatch in the currency of debt obligations and revenue, which exposes projects to the risk of devaluation over time. This can result in reduced investments due to currency risk. |

To mitigate currency or foreign exchange risk, a currency swap with a third-party provider to protect against devaluations may be used. |

|

Credit risk |

Since corporate PPAs are crucial revenue contracts, the creditworthiness of the corporate buyer is also crucial. In fact, the attractiveness and bankability of long-term corporate PPA agreements depend significantly on the creditworthiness of the corporate buyer. Credit risk covers the likelihood that the off-taker will be unable to pay amounts owed under a corporate PPA. Even where a corporate buyer has a good reputation and global brand, the creditworthiness of the particular contracting entity will be carefully scrutinised by both the developer and the lenders. |

To mitigate credit risk, lenders might require letters of credit, parent company guarantees or another appropriately sized bank guarantee from an A-rated bank. Multiple buyer structures (where there is a single corporate buyer representing the aggregated demand of a group of buyers) can also help spread credit risk (so-called 'club structures'). With club structures, a lender may develop an internal bespoke credit rating for the blended buyer vehicle, rather than rely solely or partially on third-party credit support. Multiple buyer structures involving multiple corporates, or a combination of corporates and utilities, could be a way for sellers to increase appetite for large projects, where a single, large interested buyer does not exist. |

|

Scheduling risk |

Scheduling risk relates to the deviations between forecasts of expected power production by generators to network operators and the actual outturn production. |

Typically, scheduling risk is borne by the network operators, which charge a fee for their services. |

|

Basis risk |

Where a project is located can have a major impact on risks thereto. This is commonly referred to as location risk. Numerous factors relating to location, including transmission line congestion, wind and solar intermittency and variability, market saturation and state-based or regional regulations can influence the value of a corporate PPA. One type of location risk is basis risk, which is the possibility of a mismatch between the market price at a project's delivery point and the prevailing price at the agreed upon trading point that is specified in the corporate PPA. If the buyer and developer are located in different markets and the corporate PPA payments are linked to the wholesale price in the market that is local to the developer (not the buyer), the buyer is exposed to the 'basis risk' in wholesale price movements. This risk is usually more relevant to virtual corporate PPAs, but can also be relevant in physical corporate PPAs (in markets with zonal pricings). If the retail price in the buyer's market and the wholesale price in the developer's market are not correlated, the buyer becomes exposed to volatility in retail power purchasing. |

In order to share basis risk and structure a bankable project, some virtual corporate PPAs provide for pricing adjustments (on a fixed or floating basis) or caps. Alternatively, some project owners enter into ancillary agreements with third parties to hedge the basis risk, either by their own initiative or by request of the lenders. |

|

Balancing risk |

Balancing risk concerns the need to provide a continuous supply of power to the corporate buyer. It is the risk of exposure to power system costs that arise when an asset's forecast generation is less than its actual generation. The more an asset contributes to the power system's imbalance, the higher the imbalance cost is. The more the generation profile of an asset correlates with the market-wide generation profile of its technology, the more the asset's imbalance correlates with the overall power system imbalance, resulting in higher imbalance costs. |

One way to mitigate the seller's balancing risk is through outsourcing (ie, entering into an agreement with a third party or a party belonging to the same group as the corporate buyer), which agrees to supplement for any shortfall in power production in order to meet the obligation of providing a continuous supply of power to the corporate buyer. As an alternative, the corporate buyer may execute a back-to-back electricity supply contract with a third-party provider or with the electricity utility, whereby the renewable supply is topped up with other electricity to provide the required power supply. Third parties or utilities will typically charge a fee to compensate for managing the balancing risk. |

|

Volume risk |

Volume risk captures the variability of power generation of a plant over a given period, which may be a season or a full year. The risk may derive from climatic variations, such as wind that is higher than expected one year or lower solar irradiation levels due to a cloudy summer. |

Corporate buyers will insist that the developer commits to a minimum volume over a reasonable period. Developers may agree to the extent that the minimum output requirements are achievable and aggregated over time. Failure to comply with a volume guarantee could lead to contractual damages being payable to compensate the corporate buyer for the actual cost of buying additional power. In some jurisdictions, so-called 'weather derivatives' have been implemented. |

|

Shape or profile risk |

Shape or profile risk is connected to volume risk but it captures the fact that hourly generation will be variable depending on wind speed or solar irradiation, irrespective of whether the overall volume over a given period is equal to the estimated volume. The intermittent actual generation of power from a renewable energy plant may be different from the generation forecast and inconsistent with the baseload demand of a corporate buyer (which is likely to be flatter, with a pronounced variation between business and non-business days). Developers may be willing to guarantee the mechanical availability of their plants but not actual output, as that is influenced by weather conditions and operational strategy over which they have no control. As a result, shape or profile risk has so far been considered as a risk to be managed by the corporate buyer. |

The corporate buyer may traditionally use its utility supplier as a sleeving agent to manage the variable volumes from a corporate PPA as part of the wider management of the corporate buyer's electricity demand. However, thanks to smart digital telemetry and process control, innovative buy-side mitigation tools are emerging which may allow the buyer to adapt its load on the grid to correspond to the generation profile of the renewable energy plant or imbalances on the grid. These technologies can respond to an imbalance by switching off equipment that does not immediately require power until the price spike has passed. Although there are few cases where the seller offers to manage shape or profile risk, the fact is that the seller may:

Proxy revenue swaps are hedging solutions where the hedge provider or the insurer pays the seller a pre-agreed fixed price per annum (rather than providing a fixed unit price per MWh generated or sold). The project swaps the uncertain annual volume of power that would be generated by an efficient project with a more certain payment at a fixed long-term price. Due to the need to pay up front structuring fees, annual fees and services fee to put this structure in place, hedging products may be a viable solution, particularly for larger projects. Another innovative sell-side mitigation tool for shape risk may be the integration of power storage technologies behind the metre, together with renewable energy projects. The seller can use the power storage system to smooth peaks in renewable generation, as well as to assist with imbalance costs and other technical constraints on the grid. |

|

Construction risk |

In order for new projects to be built, development or construction risk must be considered. Construction risk is risk that the plant is not completed in a timely basis or at all. |

To mitigate construction risk, a corporate buyer may negotiate adequate termination rights, withdrawal rights and damages for any significant delay in the delivery of the power caused by the developer's delay in completing the project. Developers will focus on ensuring that a project's milestones include an appropriate buffer and will extend any deadlines on the occurrence of a force majeure event or a change in law. Lenders will be aligned with the interests of the developers and will carry out due diligence on both the project and the developer to evaluate the risk that that the corporate PPA may be terminated before a project is completed. |

|

Performance or operating risk |

Performance or operating risk is the risk that the project does not perform as expected in terms of the level of mechanical availability, warranted power curve (wind) or performance ratio (solar photovoltaics). |

Corporate buyers may demand withdrawal rights from a corporate PPA in the event of poor project performance. Developers may try to deny demand for performance guarantees and argue that they are unnecessary in light of the economic incentive on a generator to maximise production. If a performance guarantee is agreed, developers and lenders will focus on ensuring that any requirements are reasonably achievable and that the contract also provides for cure rights. Developers will also seek to pass this risk to contractors in the supply chain. |

|

Change in law risk |

During the construction or operation of a project or during the term of a contract, a change in law or a force majeure event may occur. Change in law risk captures the risk that developments in applicable legislation and regulation may upset the balance of risks and rewards under a corporate PPA. |

Developers will insist on having a mechanism to renegotiate material provisions of a corporate PPA that may be impacted by a change in law. Such mechanism will seek to restore the agreement to the original economic intent, especially where the corporate PPA is the primary revenue resource for a project. A corporate buyer will resist this, especially in case of a fixed-price corporate PPA, on the basis that the fixed price justifies the project bearing this risk. Lenders will be focused on one thing: ensuring that any change in law does not materially undermine the project's forecasted revenues. |

|

Force majeure risk |

Force majeure risk is the risk that extraneous events may occur over which the developer or the corporate buyer have no control (including acts of God or extreme weather conditions) and which may delay completion of a project or affect its power generation capabilities. |

A corporate buyer will focus on ensuring that the seller is required to use its best efforts to remedy any delay or negative impact caused by a force majeure event. The corporate buyer will also demand the right to purchase power from an alternative source, as required. Corporate buyers may also demand the right to withdraw from the corporate PPA if the force majeure event extends for a considerable period. On the other hand, developers will try to negotiate a long remedy period for any force majeure event before the corporate buyer has the right to terminate a corporate PPA. Developers will also want a corporate PPA to provide that certain types of construction delay and facility underperformance are considered force majeure events. A fair allocation of the force majeure risk between the corporate buyer and the developer is in the best interests of all the parties to the corporate PPA, including the lenders. |

At present, key markets for the development of corporate PPAs are Latin America, Northern Europe, India and Singapore, which share the following common features:

- a compatible renewable subsidy;

- high and volatile wholesale electricity prices;

- availability of renewable resources; and

- electricity demand growth from company operations.

Whether corporate PPAs will be implemented to the same extent and with the same success in Italy as in the countries listed above is yet to be seen.

However, the use of long-term corporate PPAs in Italy looks likely to increase and they look set to play an important role in the clean energy market and relevant regulation. The decline in the availability of government-backed fixed feed-in tariffs at a premium to the wholesale market will almost certainly increase the appetite for corporate PPAs, although the market demand for corporate PPAs alone is unlikely to deliver the INES without other, complimentary regulatory intervention.

As the market for the development of subsidy-free renewable energy projects grows, corporate PPAs are expected to become a common part of the energy and sustainability strategies of Italian corporates.

Endnotes

(1) The full version of the INES is available here.

(2) For the full text of the new draft decree-law please see here.

This article was first published by the International Law Office, a premium online legal update service for major companies and law firms worldwide. Register for a free subscription.