On 1 February 2020 Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman presented the Union Finance Budget 2020-21. This was the minister's second budget and it had been eagerly awaited, as the government is facing immense criticism for failing to revive the slowing Indian economy.

On 31 January 2019 the government tabled the Economic Survey for the 2019-20 financial year before Parliament. In line with the government's vision of a $5 trillion Indian economy, the survey's main theme was 'wealth creation'.

The survey highlighted the historic role that wealth creation has played in growing India's economy. Further, it stressed the promotion of pro-business policies that unleash the power of competitive markets to generate wealth while turning away from 'pro-crony' policies that may favour specific private interests. Much was expected from the budget to lead the way forward to a resurgent economy. However, the lack of positive and 'big ticket' reforms may leave promoters and family businesses disheartened.

Reduced tax rates

While providing individuals and Hindu undivided families (HUFs) the option to continue to be taxed under the current regime, the government has proposed the following changes to the tax rates.

|

Total income |

Existing tax rates |

Proposed tax rates |

|

Up to Rs250,000 |

Nil |

Nil |

|

Rs250,001 to Rs500,000 |

5% |

5% |

|

Rs500,001 to Rs750,000 |

20% |

10% |

|

Rs750,001 to Rs1 million |

20% |

15% |

|

Rs1 million to Rs1.25 million |

30% |

20% |

|

Rs1.25 million to Rs1.5 million |

30% |

25% |

|

More than Rs1.5 million |

30% |

30% |

The amendments are proposed to take effect on 1 April 2020.

Eligibility conditions

The abovementioned concessional tax rates would be subject to the following conditions:

- The income under this scheme will be calculated without claiming any of the deductions provided under the Income Tax Act 1961. Some of the key deductions which will no longer be available under the new regime are:

- the leave travel concession;

- the house rent allowance; and

- the charitable trust donation allowance.

- Any carry-forward losses from earlier assessment years cannot be offset if such loss is:

- attributable to a deduction under the Income Tax Act; or

- a 'house property' loss with any other head of income.

- Depreciation must be claimed in the manner specified in the act.

The above proposal is likely to complicate the personal tax regime for small tax payers due to multiple combinations that may be available to them. For example, the new regime might be beneficial for foreigners who live and work in India for a short period because such individuals are not inclined to opt for investment-based deductions in India. However, as most taxpayers claim various deductions in their tax returns, they would need to pay more tax under the new regime.

These changes provide no respite to high-net-worth individuals (HNIs) who choose to be taxed under the new regime (foregoing their deductions), as they will remain in the highest tax bracket.

Change in tax residency rules

In India, tax is levied based on the taxpayer's residence and source of income. Indian residents are taxed on their worldwide income, while non-residents are subject to tax only on income accruing from India.

Changes to residency rules of citizens or PIOs

The act specifies certain tests to determine tax residency. Under the existing regime, an individual will have been a resident in India in the previous year if they were in India for:

- a total of 182 days or more; or

- 60 days or more and 365 days over the course of the four years preceding that year.

Where the taxpayer is an Indian citizen or a person of Indian origin (PIO), the requirement to have spent 60 days or more in India in the previous year is extended to 182 days.

Under the proposed regime, where the taxpayer is an Indian citizen or a PIO, the requirement to have spent 60 days or more in India in the previous year is extended to 120 days. This change considers the high number of HNIs who have taken advantage of the provision to carry on substantial economic activities in India without qualifying as Indian tax residents. This is a bold move by the government which shows its continued intent to scrutinise HNIs and its attempts to curb the practice of taxpayers misusing the higher threshold.

Citizenship-based tax

In a revolutionary move by the government, the budget proposes that Indian citizens will be deemed to be Indian tax residents if they are not liable to pay tax in any other country by reason of domicile or residency or any other criteria of a similar nature, regardless of whether such an individual meets the Indian tax residency test set out above. Further, the Central Board of Direct Taxation's 2 February 2020 press release has clarified that any person who qualifies as an Indian resident pursuant to the proposed amendment would be subject to tax in India only on income derived by them from an Indian business or profession. Thus, persons who qualify as tax residents in jurisdictions with more favourable taxation, such as Indian citizens working in Dubai or Abu Dhabi, would not be subject to tax in India.

Further relaxation of taxation of individuals not ordinarily resident in India

The Income Tax Act currently provides that individuals or HUFs are treated as not ordinarily resident in India in the relevant financial year if they did not reside in India for nine of the 10 years preceding that year or for an overall period of 729 days during the seven years preceding that year.

Under the proposed regime, individuals or HUFs are treated as not ordinarily resident in India in the relevant financial year if they did not reside in India in seven of the 10 years preceding that year. Such persons would be subject to tax in India only on income accruing from India and not on their worldwide income.

These amendments will take effect from 1 April 2020.

What do these changes mean in practice?

All of these changes signal a major shift in India's tax policy towards a more aggressive approach. India is trying to emulate the United States, which taxes its citizens irrespective of their tax residence.

As regards the changes to residency, individuals should be careful when planning a visit to India. Indian citizens who visit India for more than 120 days or are not liable to pay tax in any other country will be regarded as 'resident' in India and taxed there accordingly. Understandably, this is something that all global HNIs would like to avoid. This becomes especially important for those who have settled in the United States or the United Kingdom but continue to return to India frequently (eg, to manage their assets or visit family).

Abolition of dividend distribution tax

Under the Income Tax Act, the distribution of dividends by a domestic company is subject to an additional income tax called dividend distribution tax (DDT) in the hands of the company at an effective rate of 20.56% (including surcharge and cess). Further, an additional 10% tax is levied on dividend income in excess of Rs1 million.

The act also provides for a similar regime for mutual funds, whereby such funds are liable to pay additional income tax at the specified rate on any income distributed by them to their unit holders.

The budget proposes to abolish the DDT regime and reintroduce the classical method of taxing dividends. The budget sets out the following proposals in this regard.

Abolition of DDT: dividend income taxable in hands of receiver

The budget proposes to amend the act to provide that DDT will not apply in relation to dividends declared, distributed or paid by a domestic company after 31 March 2020. Accordingly, such dividends would not be exempt in the hands of the shareholders. Similar amendments have also been proposed in respect of income distributed by mutual funds. The budget also proposes to delete the imposition of the additional 10% tax.

Withholding tax

The budget proposes to amend the act to impose a 10% withholding tax on all dividends paid by an Indian company to a resident shareholder. Further, it proposes to amend the act to introduce a 20% withholding tax on dividends paid to non-residents.

Deduction for intercorporate dividends

The budget proposes to introduce a deduction on dividends received by one domestic company from another in calculating the total income of the shareholder company. However, this deduction would be limited to the amount of dividend distributed by the investee company before the due date (ie, one month before the date of furnishing the return).

Deduction of expenses The budget proposes to amend the act to allow a deduction on expenses in relation to dividend income to the extent of 20% of the dividend received, in computing the income under the head of 'other incomes'.

Impact on HNIs

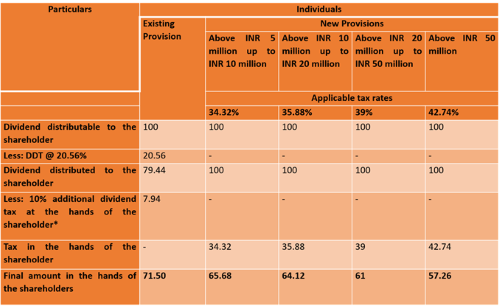

The below table sets out the impact of the above changes.

Figure 1

The additional tax, as explained above, would apply only to shareholders whose dividend income exceeds Rs1 million. The 10% additional tax rate is exclusive of applicable surcharge and cess.

As the applicable effective personal income tax rates of HNIs is extremely high (currently 42.74%), the abolition of the DDT and taxation of dividend income at the individual shareholder level will not have a major impact. Previously, such persons were exempt from being taxed on any dividend income received by them and were suddenly subject to tax at the maximum marginal rate (MMR) of 42.74%.

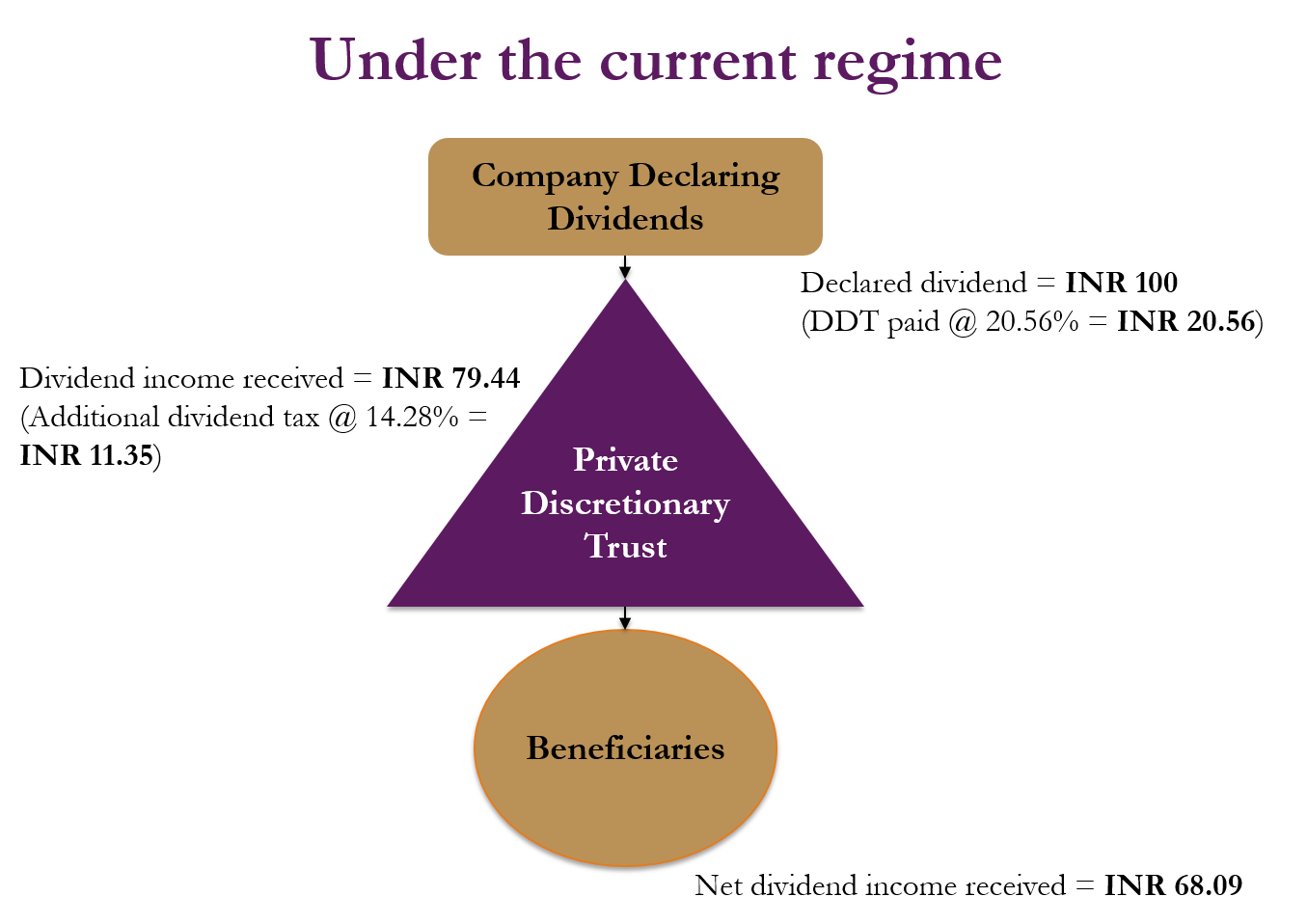

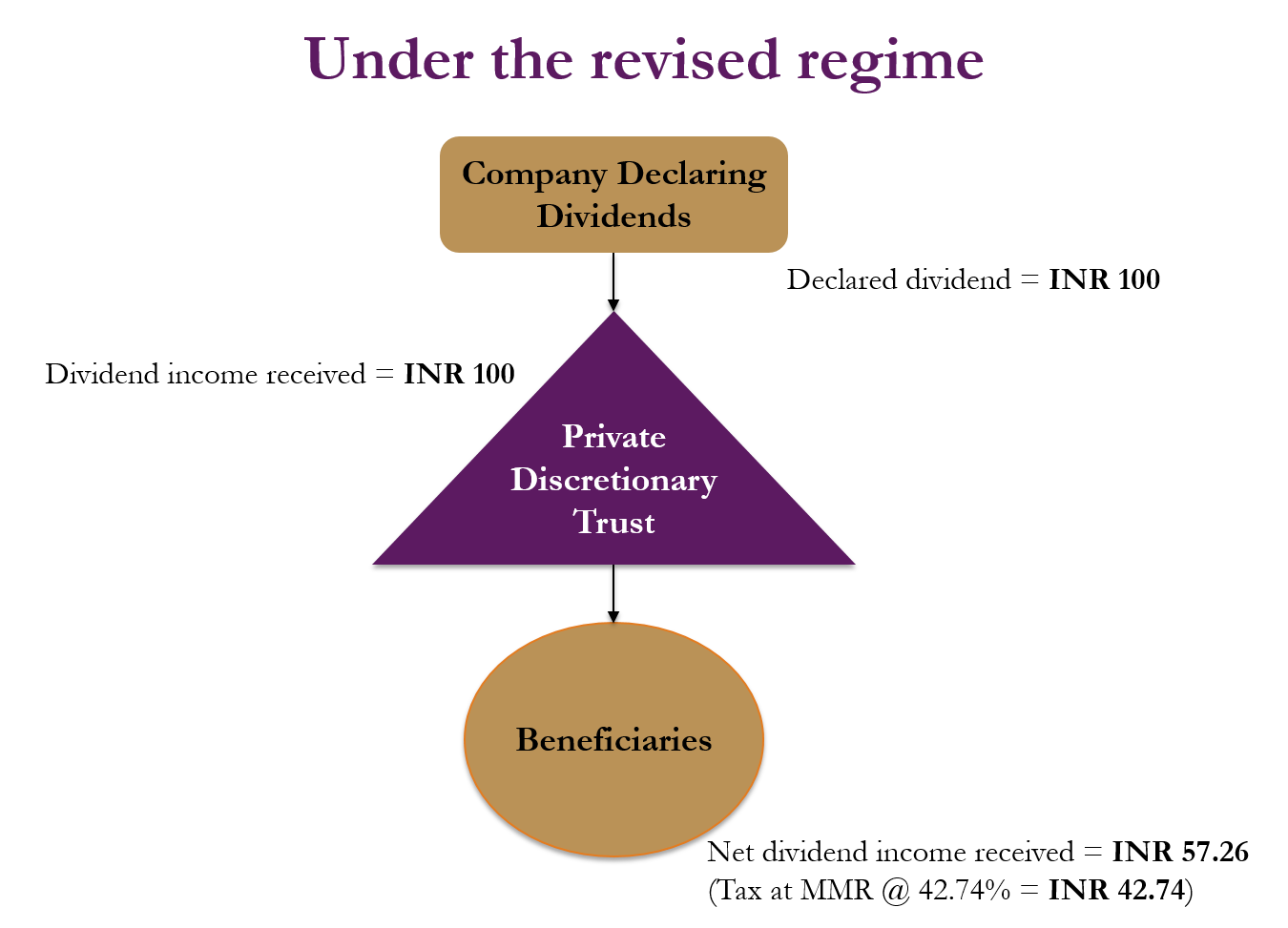

Impact on private discretionary trusts

The recent abolition of DDT in the hands of the company and the taxability of such dividends in the hands of shareholders is especially painful for private discretionary trusts and associations of persons (AOPs). Trusts and AOPs are subject to tax at the MMR. However, apart from the tax disadvantage, the viability of trusts against an insolvency attack from disgruntled creditors or the potential threat of estate duty must also be considered. For some, the high tax incidence may be outweighed by other protections that a trust can afford.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Impact on foreign investors and shareholders

Non-resident investors would be able to not only take advantage of the lower tax rates specified in the double taxation avoidance agreements, but also claim credit for tax paid in India against the tax payable in their country of residence. These amendments are proposed to take effect on 1 April 2020.

Further boost for start-ups

Extended tax holiday

The budget sets out the following proposals to take effect from 1 April 2021.

|

Existing regime |

Proposed regime |

|

Income earned by start-ups is eligible for a 100% tax exemption for three consecutive years out of seven years, at the option of the assessee. |

Income earned by start-ups is eligible for a 100% tax exemption for three consecutive years out of 10 years, at the option of the assessee. |

|

This provision is limited to companies whose total turnover does not exceed Rs250 million. |

This proposal is extended to companies whose total turnover in any year since its incorporation did not exceed Rs1 billion. |

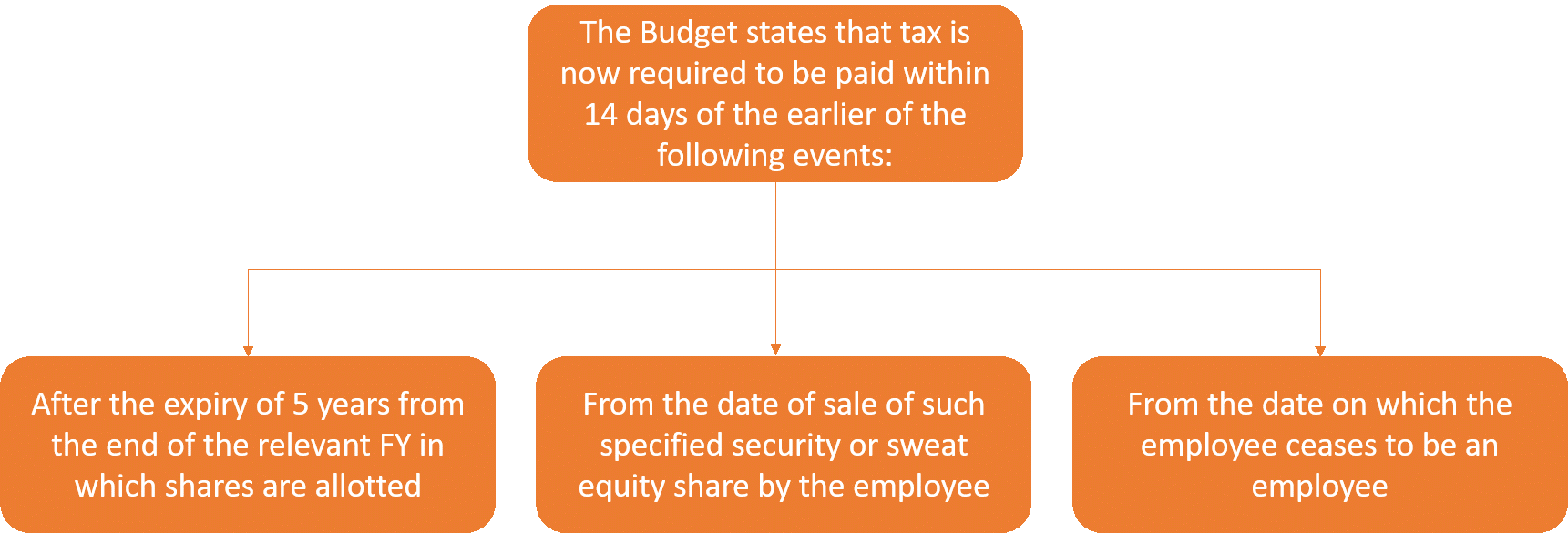

Deferring TDS or tax payment in relation to ESOPs

Under the current regime, employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs) are taxed on two components:

- tax on perquisite as income from salary at the time of exercise; and

- tax on income from capital gains at the time of sale.

Figure 4

These amendments will take effect from 1 April 2020. However, such deferred payment rules will apply only to ESOPs issued to employees of start-ups and will not extend to all corporates.

The finance minister's budget speech was perceived as a nod towards the possibility of significant promoter-friendly policies being introduced through the budget. However, on an examination of the changes introduced by the budget, it appears that the government has failed to translate these ideals into actions. While there are a few positive changes, overall, the budget seems to represent a missed opportunity.