On 20 November 2020 the 75th session of the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) approved a ban on the use and carriage of so-called 'heavy fuel oil' ('HFO') in the Arctic. The new regulation amends the International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters (the Polar Code), as implemented in the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL). The proposed amendments are expected to be formally adopted at the next MEPC session in June 2021. However, more stringent standards have already been proposed by the Norwegian government for the area surrounding Svalbard.

Although there is no clear definition of 'HFO', it is generally said to be a category of fuel oils with a particularly high viscosity and density, making it nearly tar-like. Therefore, HFO behaves differently than other fuels when released into water. Spills of HFO are of particular concern in polar waters as:

- the biological weathering generally takes longer;

- the HFO may solidify and sink, get trapped under and in ice and be transported over long distances; and

- clean-up is especially onerous in dark, cold and icy Arctic conditions.

Therefore, the oil will remain in the environment for a long time and may have devastating and lasting effects.

In addition, the combustion of HFO leads to some of the highest levels of exhaust emissions of all marine fuels, including black carbon emissions, which, when deposited in snow and ice, reduces the surface albedo and contributes to so-called 'Arctic amplification', a combination of feed-back processes speeding up the melting of sea ice and creating warmer temperatures in the region. Although HFO is not the most-used fuel in the Arctic, its use is reported to have increased more than any other type of fuel in the region in recent years.

While only recently agreed, the draft amendments have already been heavily criticised for not being effective enough and offering too many wavers and exemptions. Apparently, the proposed IMO ban was not considered sufficient by the Norwegian government either which, shortly before the new regulations were approved, put out on hearing national legislation which would ban all use of HFO in the waters surrounding Svalbard. Therefore, the exact extent of future fuel standards in the Arctic remains to be seen, and the regulations may vary.

Polar Code and current pollution standards

On 1 January 2017 the Polar Code entered into force. It prescribes mandatory minimum standards and non-mandatory guidelines regarding safety and pollution prevention for vessels operating in both Arctic and Antarctic polar areas. It was adopted through amendments to the International Convention on Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) and MARPOL and has a supplementary function to existing IMO instruments. Its supplementary function means that, among other things, the new and stricter IMO regulations in MARPOL concerning the sulphur content of ships' fuel oil (IMO 2020) also apply to vessels operating within the Polar Code's geographical scope. This is also the case for other IMO measures to fulfil the organisation's goal of a 50% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from international shipping compared with 2008 levels by no later than 2050.

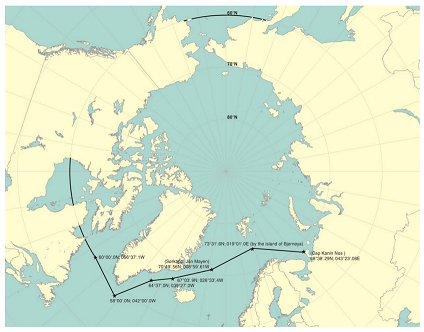

Figure 1: The Polar Code's geographical scope, IMO

Mandatory pollution measures are prescribed in Part II-A of the Polar Code, which amends MARPOL Annexes I, II, IV and V. Part II-A prohibits and regulates discharges into polar waters. Spread out in different MARPOL annexes, the Polar Code:

- fixes a ban on "any discharge" of oil or oily mixtures (Annex I) and noxious liquid substances (Annex II) into the sea;

- prescribes operational requirements and prohibitions to prevent pollution by sewage from ships (Annex IV); and

- prohibits the disposal of any garbage, cargo residue and food waste in ice-covered areas (Annex V).

The amendments to SOLAS prescribe new and stricter safety provisions for ships operating in polar waters, including for equipment, design, construction, operation and manning.

Approved ban on HFO in Polar Code

Ever since HFO was banned for carriage in bulk as cargo, use as ballast or carriage and use as fuel in the Antarctic in 2011, a ban on HFO has been anticipated in Arctic waters. Therefore, on approval, the Polar Code was criticised for not prohibiting the use of HFO in the Arctic.

Part of the reason that it took so long to adopt the new ban is because Canada and Russia have been fearing the impact on their energy supply to local communities and shipping of commodities. This also explains the Arctic HFO ban's current form, with exemptions and waivers that have been subject to heavy criticism from environmentalists ever since the first draft was released.

There are several aspects of the approved ban which lead to questions on its efficiency. First, it prohibits only the "use and carriage" of HFO as "fuel" and not "the carriage in bulk as cargo [and] use as ballast", as the Antarctic ban does. Second, it will come into effect on 1 July 2024, which means that there will be a more than three-year grace period after what is expected to be its formal adoption.

Further, it offers exemptions from the ban for certain newer vessels with a gap of at least 76cm between the fuel tank and the outer hull of the ship. This gap – even though it may provide some protection – might nonetheless fail to prevent oil spills, provided that the damage is serious enough. These exemptions last until 1 July 2029.

Finally, states bordering Arctic waters can "waive the requirements of [the HFO regulation] for ships flying the flag of the Party while operating in waters subject to the sovereignty or jurisdiction of that Party" until 1 July 2029. In other words, according to the Polar Code's definition of 'Arctic waters', Norway (because of Svalbard and Jan Mayen), among other countries, may waive the obligation to not carry or use HFO as fuel in its territorial seas and exclusive economic zones until 2029.

The exemptions and waivers are potentially substantial. At present, it is primarily vessels with an Arctic flag that use HFO in the region. A study conducted by the International Council on Clean Transportation suggests that "had the proposed HFO ban been in place in 2019, exemptions and waivers would have allowed as much as 70% of HFO carriage and 84% of HFO use to remain in the Arctic"(1) – making the ban potentially toothless for nearly another decade.

Proposed Norwegian ban of HFO in waters around Svalbard

On the other hand, Norway shows no desire to utilise the right to waive the Polar Code requirements in its waters. Simultaneously, as environmentalists were heavily criticising the proposed Polar Code ban, the Norwegian government ceased the opportunity to put out on hearing a proposal for a full ban on HFO in the waters around Svalbard.

The proposal is an amendment to the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act (SEPA), which already bans the carriage and usage of HFO by all ships in the natural parks in Svalbard. The current ban is stricter than the one in the Polar Code as it also bans the use of hybrid oil (which may be as dangerous to the environment as heavy oil).

The new Norwegian proposal states that ships "calling at" the territorial sea around Svalbard must not use or carry on board petroleum-based fuel other than natural gas and marine gas oil. 'Marine gas oil' and 'natural gas' will be more closely defined by regulation. The ban – if passed by Parliament – is expected to enter into force on 1 January 2022.

The proposal has been praised by environmental organisations for being stricter than the Polar Code, as it prescribes a ban not only on traditional HFO but also on hybrid oil, in all of Svalbard's territorial sea and without any substantial waivers and exemptions, entering into force as early as 2022. The consultation paper for the proposal suggests that should the ban be put in place at present, it would have consequences for cruise vessels, bulk vessels, refrigerator ships, cargo ships and fishing vessels currently operating in the Svalbard region.

An expansion of the current SEPA ban seems reasonable. An oil spill does not follow borders and a spill outside the Svalbard natural parks might spread easily to these areas that are in need of particular protection. However, parties might question whether such a ban is in accordance with international law and, in particular, the right to "innocent passage" prescribed in Article 17 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). However, it is likely that a ban for any vessel calling at a port or roadstead in Svalbard is lawful in accordance with the principles of port state jurisdiction. Further, based on the consultation paper, it would appear that the use of the wording "call at" would mean that the ban would not apply to vessels performing innocent passage, continuous and expeditious through the territorial sea (Article 19 of the UNCLOS).

Many developments relating to emission and fuel standards in the Arctic took place in 2020. A ban on the use of HFO in the Arctic has been in the pipeline for a long time and will finally be adopted in 2021. Even though the IMO is beefing up its emission and fuel standards in the Arctic, with its waivers and exemptions it is clear that the ban is far from bulletproof. It remains to be seen whether other states will follow Norway's lead and propose similar bans in their waters. This would ensure harmonisation of the standards in the region, which in turn would the benefit both the environment and the shipping industry's predictability.

Endnotes

(1) Available here.